CAPE FLATTERY, Wash., May 21, 2023—Nearly 150 years ago, the SS Pacific and the S/V Orpheus collided off the coast of Cape Flattery in Washington state. While the Orpheus was able to ready lifeboats and make necessary repairs, the SS Pacific was not so fortunate, sinking into the late-night waters killing all but two of its estimated, 325 passengers. To this day, the incident remains one of the deadliest maritime disasters in Pacific Northwest history.

For years, the remains of the SS Pacific sat on the ocean floor, near the Strait of Juan de Fuca. As sonar technology improved, a man by the name of Jeff Hummel formed Rockfish Incorporated and the Seattle-based Northwest Shipwreck Alliance, both set on locating the historic wreckage.

Hummel’s search commenced in 1993, interviewing countless commercial fisherman, and calculating wind currents, until a discovery was finally made late last year using Wave WiFi and the Starlink satellite system. After being granted salvage rights by United States Court Judge James Robart of the Western District of Washington, Hummel will finally begin the long-awaited recovery of the doomed historic steamship this year around September or early October.

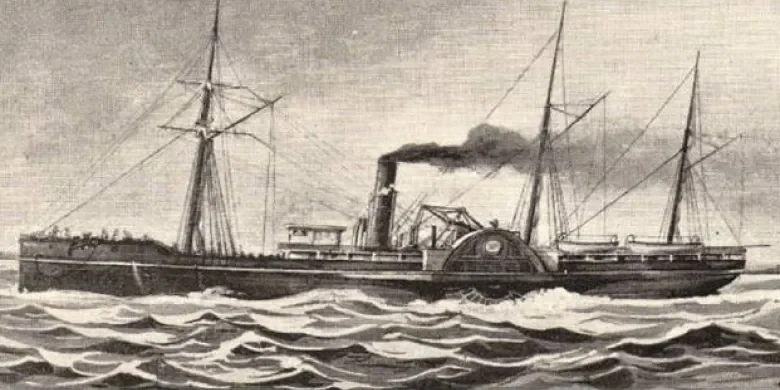

The sinking of the S.S. Pacific Steamer

The 223-foot SS Pacific steamer departed from Esquimalt Harbor in Victoria, British Columbia, in the November of 1875. The weather conditions were poor and the vessel was known to have difficulty keeping an even keel earlier in the evening of the crash. To correct this issue, the crew filled the ship’s many lifeboats with water.

There were an estimated 325 passengers onboard, comprised of 52 crew — including Captain Howell at the helm — 35 passengers from Puget Sound ports, and another 132 ticketed passengers who embarked in Victoria. There was also an unknown number of unticketed passengers who rushed onboard and the number of children, who were able to sail for free, could not be tracked due to them not being issued a ticket. The passengers varied from prominent Canadians, wealthy businessmen, gold miners, and about 41 unidentified people of Chinese descent.

According to Northwest boating publication Waggoner, the ship also carried 300 bales of hops, 2,000 sacks of oats, 250 hides, 11 casks of furs, 31 barrels of cranberries, 2 cases of opium, six horses and two buggies, 280 tons of coal from Puget Sound, 30 tons of miscellaneous goods, and $79,220 in gold — all of which is valued today at an estimated $10 million.

On November 4 of that year at approximately 10 p.m., another vessel, the Orpheus, which was on its way to San Francisco to pick up coal, collided with the SS Pacific causing the ship to split in two. Survivors recalled that the torn smokestack of the Pacific collapsed on the capsized vessel.

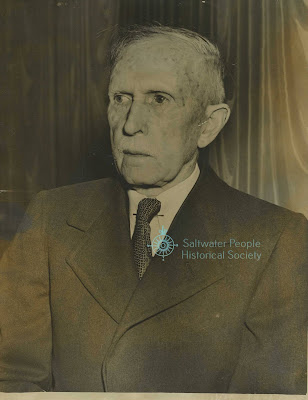

Photo dated July 1942. Saltwater People Log

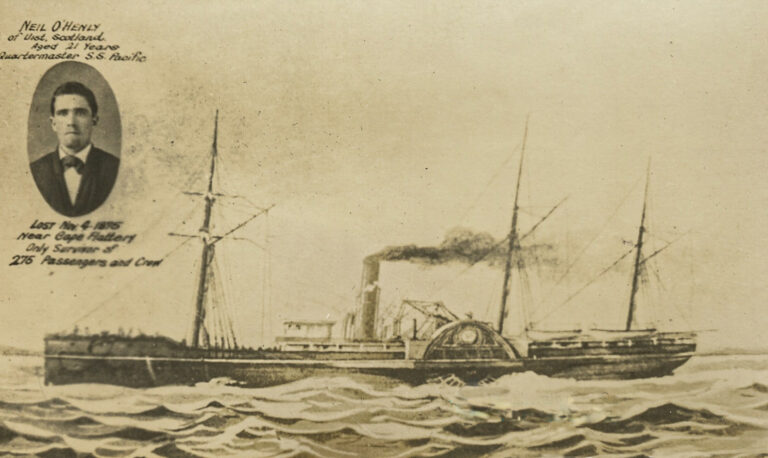

“I woke up with the crash. Jumped out of my bunk, the water rushing through the bow; saw all hands rush on the hurricane deck… the ship fell into the trough of the sea and became unmanageable, the fires being extinguished; all was confusion, the passengers crowding into the boats which the officers and crew were trying to clear away,” said Neil Henly, Quartermaster aboard the Pacific and one of the two survivors, according to The Northwest Shipwreck Alliance.

The crew of the Orpheus made the fatal mistake of turning the ship port (or left) placing their trajectory directly in the lane of the SS Pacific’s course. They were simply obeying their captain’s orders, Charles Sawyer, whose last command was to “starboard the helm” if a light was seen before disappearing into the cabin to study charts. Captain Sawyer was, of course, referring to the “light” of the Cape Flattery Lighthouse, which meant they would turn towards the Straight, and not the light of another ship, however.

The Pacific did not see Orpheus until it was too late. As it became clear the ship was going down, passengers scrambled on the ship’s many lifeboats but, since they were filled with water to correct the uneven keel, they would not keep afloat; immediately filling with water and sending the ill-fated passengers to their deaths.

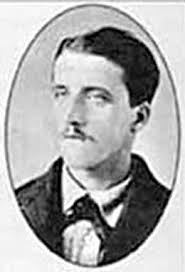

“[I] tried to get the boat off, but we could not budge the boat; … the boat I was near was partly full of water; we could not get her off at all; I think it was about an hour from the time the steamer struck up to the time when she listed to port so much that the port boat was let into the water and cut loose from the davits; I was in this boat which, when it touched the water, began to fill and turn over. I crawled up on the bottom of the boat and helped several others up with me … I think about all the ladies were in our boat, and when she upset, they all fell into the water and, I fear, they were all drowned,” Henry L. Jelly, the second survivor accounted.

Jelly was the first survivor to be rescued. He was found two days after the crash, floating on a broken piece of wood, by the vessel Messenger. Jelly’s report of the incident was the first indication the Pacific had sank; Not even the crew aboard the Orpheus knew. In response, several rescue boats scanned the area and found Henly two days later, also floating on a piece of broken ship, by the rescue vessel Walcott.

The SS Pacific was owned by Goodall, Nelson and Perkins Steamship Company. Later the company changed its name to the Pacific Coast Steamship Company to separate itself from the maritime disaster. For years the company grew and became an important steamship line on the west coast but financial difficulties during the Great Depression caused the company to ultimately dissolve in 1938.

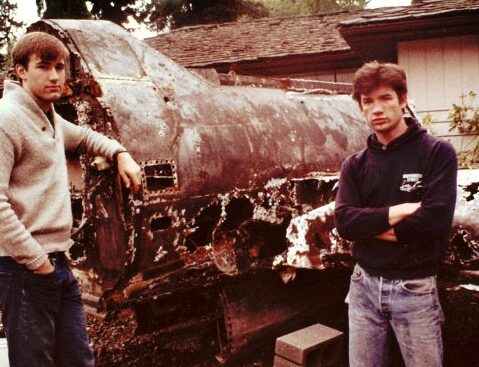

Friends Jeff Hummel and Matt McCauley

Jeff Hummel and Matt McCauley first met while attending a high school in Mercer Island in 1979. In conversation, Hummel brought up a sunken airplane he knew about, which his father witnessed crash in Lake Washington while working at the Boeing plant in Renton. Having recently received their scuba certifications, the two thought it would be a fun project to recover the sunken World War II Navy aircraft together.

Both knowing the Navy had ownership of crash sites, they wrote a letter to the Pentagon asking for permission to retrieve the plane. When the Pentagon responded they had no protocol regarding intentionally discarded planes, the men interpreted it as their project was green-lit.

The two succeeded in their mission, using old gas station air hoses and lift balloons, to retrieve the sunken plane. Originally intending to transport it to a local hangar, the aircraft ended up in McCauley’s front yard as a sort of roadside attraction for some time.

But it turned out the Navy did care about intentionally discarded planes. In 1984, when Hummel and McCauley were just 20 years old, they were sued by the United States Navy (United States v. Hummel). In 1985, the two divers won their case, with the federal judge ruling that the Navy’s treatment of the particular Helldiver aircraft constituted intentional abandonment which awarded them free title to the plane which is currently being restored and is expected to fly again soon.

Hummel and McCauley went on to recover four more WWII-era naval combat aircraft from Lake Washington in 1987, and several wreck projects since. This interest eventually led to forming the Northwest Shipwreck Alliance in 2021, dedicated to locating, recovering, and preserving historic shipwrecks in the Pacific Northwest waters.

Major breakthroughs and Starlink for better sonar connectivity

Although Hummel’s interest in locating the SS Pacific began in 1993, his first major breakthrough was in the early 2000’s when a commercial fisherman brought up some old coal in a fishing net. The coal was analyzed in a laboratory and was identified to be the same coal used on the SS Pacific, that is, coal used in the Libby Mine out of Pierce Bay.

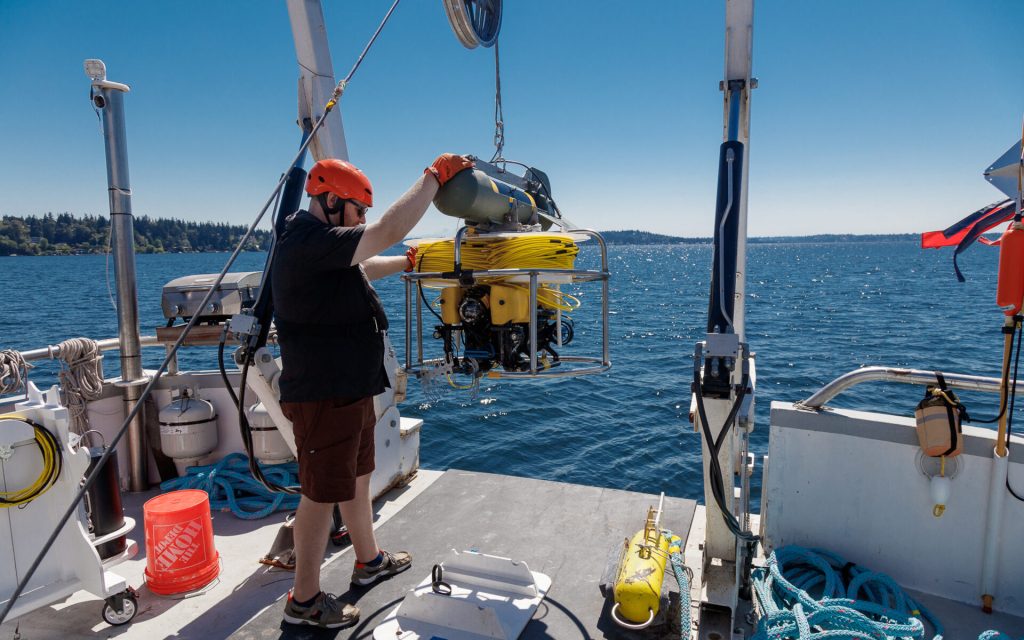

The next major breakthrough was in the fall of 2022 when a firebrick from the Pacific’s boiler room and a piece of its hull were successfully brought up by ROV operator, Sarah Haberstroh. These two pieces were key components when Northwest Shipwreck Alliance sought salvage rights in district court.

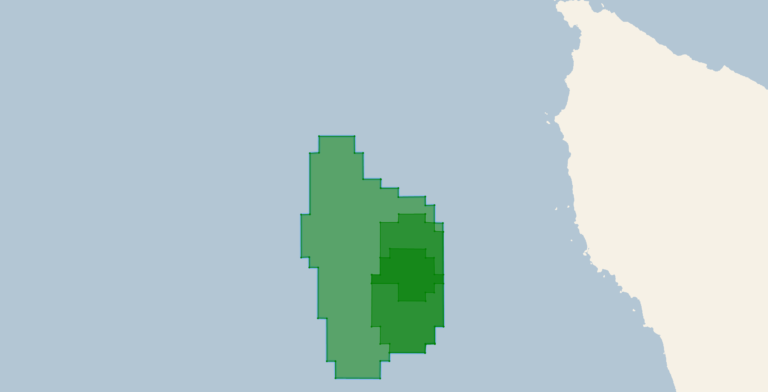

With these developments, Hummel was able to narrow his search to approximately 23 miles off the Washington coast, across a slope of 1,000 to 3,000 feet deep, where he finally found it — the SS Pacific!

Prior to Starlink being available to boaters, the crew relied on scanty cellular reception, which can often be erratic and unreliable in the vicinity of the search. Since the Starlink system became available, the crew was able to get better data speeds that, when used with a hotspot or Wave WiFi MBR 550, coverage became much more consistent.

“What we’ll be able to do is we’ll have one ROV team onboard at all times, and they’ll be there in case we need to do a repair or maintenance, but the majority of our ROV operators will be on land, operating through Starlink, low-latency, at a command center in Seattle,” Philip Drew, spokesperson for the Northwest Shipwreck Alliance, told the Lynnwood Times. “A big piece of that is it creates accessibility for people, and it allows us to work twenty-four-seven with multiple crew operating at the same time.”

ROV stands for remotely operated underwater vehicle which the SeaBlazer, the ship being used for the initial debris removal, plans to deploy this September when sailing conditions in the area calm. While the SeaBlazer’s crew (Jeff Hummel, Sarah Haberstroh, Keith Baker, and Matt McCauley) wait for more approachable sailing conditions they plan to go take to the waters of Puget Sound daily to master their new equipment.

One of the major challenges encountered in their search, and the primary reason the delay in recovery efforts, is the conditions of where the SS Pacific sank — even in the best times of year, there are 9-foot-tall waves. Also, sonar equipment is designed for much calmer waters.

“I think the longest the crew had gone with a weather window, throughout the several year search, was about nine days,” said Drew.

Salvage rights and excavation timeline

On November 22, 2022, United States District Court Judge Robart of the Western District of Washington granted exclusive salvage rights to local exploration company, Rockfish, Inc. and by extension, the non-profit Northwest Shipwreck Alliance. This ruling allows exclusive search and recovery efforts from the shipwreck of the SS Pacific.

The judge’s decision granted a team of scientists, historians and longtime crew volunteers a deadline to come back with salvage plans that will “make sure we have prepared for the highest standards of archeological protection for the historic remnants to be found”, said Hummel.

Northwest Shipwreck Alliance has said that if there are successors with interest in the ship, gold-laden with millions of dollars worth of treasure, they will have an opportunity to present their claims to the court for a limited time period.

“Private belongings onboard the ship are covered under the law of finds. Claimants are entitled to their goods provided they have proof of ownership and make a claim within the allotted time. The salvor is entitled to a healthy portion of the value of any claimed item for rendering assistance and saving the item from marine peril,” Northwest Shipwreck Alliance wrote in a press release.

But gold is not the only valuable item the SeaBlazer expects to find from the sunken SS Pacific’s site. One of the first pair of Levi’s jeans, for example, has the potential to be found since Levi Strauss developed his first pair in 1853 out of San Francisco for mostly gold miners; many of the passengers aboard the SS Pacific were gold miners from San Francisco.

“Even finding one pair of those jeans would be incredible but we think we have an entire boatload, an entire time capsule, of artifacts from that era. The team is working really hard to develop equipment to bring those artifacts to the surface and preserve and restore them,” Drew told the Lynnwood Times. “One of the most exciting pieces of this project is finding little pieces of history that connect to individual stories and families and we take that really seriously.”

Principles in laws pertaining to lost ships and their cargo date back over a thousand years. The main objective is to entice salvors to rescue ships and their cargo from peril and to return these items to commerce. Today’s salvage protocols require protections to the historical value of the site.

As for human remains — although unlikely given the depth, time, and current of the site’s location — the nonprofit said all remains will be repatriated to the port of departure, in this case Victoria, British Columbia.

The Northwest Shipwreck Alliance plans to open a maritime history museum sometime in the near future, with the SS Pacific and all of its artifacts, showcased as its centerpiece.

Author: Kienan Briscoe

3 Responses