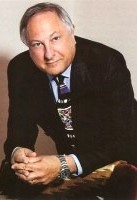

LYNNWOOD—Lynnwood resident Dennis Gibb, Vietnam veteran, former stockbroker, and convicted felon now-turned author, is set on rebuilding his life and making amends for his crimes by assisting fellow veterans to re-enter society after prison.

Gibb has just released his second published novel, An Da Shelladh, the sales of which, he says, will 100% be used to pay back the money he stole from his clients through a Ponzi scheme he managed at his former brokerage firm.

Gibb’s father was a career Army officer who served in WWII and Korea, before retiring as a Colonel in 1960. Because of his father’s career, the family moved frequently throughout the country. After returning from Korea, he was given command of an anti-aircraft missile battalion protecting the steel mills in western Pennsylvania. The family lived in Johnstown for 10 years where Dennis graduated from high school in 1964 before graduating from the University of Iowa in 1968.

Gibb enlisted in the U.S. Army that year, immediately after graduating university, and then was initially commissioned as a Field Artillery Officer before undergoing flight school to become a helicopter pilot.

“I thought at that point I was headed toward Vietnam because I was a helicopter pilot and a field artilleryman and they needed both over there,” said Gibb.

The Army sent Gibb to Fort Ord, California, instead, where there was neither aviation nor field artillery, and his responsibility was to train infantry troops.

“When I went to Fort Ord, the only thing I knew about infantry was their brand insignia,” said Gibb.

Gibb trained infantry soldiers for about a year. In July of 1971, while working as Officer of the Day on an assigned post, Gibb came across a couple of individuals breaking into an armed weapons storage facility. When he confronted them, one of the individuals began to run. Gibb commanded them to stop and, when they didn’t, he drew his pistol and fatally shot one of them. The man was an 18-year-old civilian on the base illegally.

Because of that incident, Gibb was Court Marshalled by the Army before a citizen authority could try him for murder charges. He was found innocent and, as a result, was ordered to go to Vietnam.

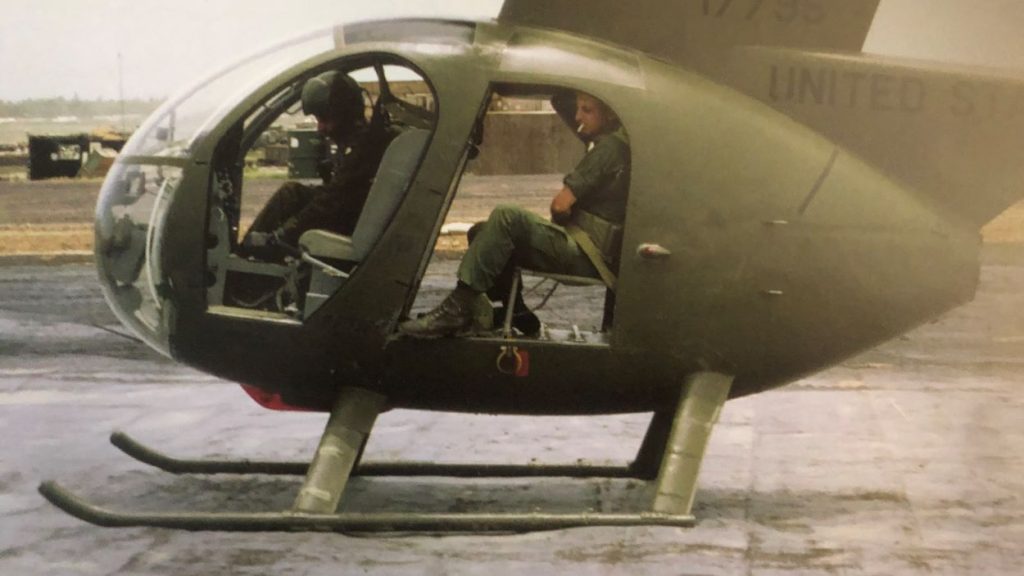

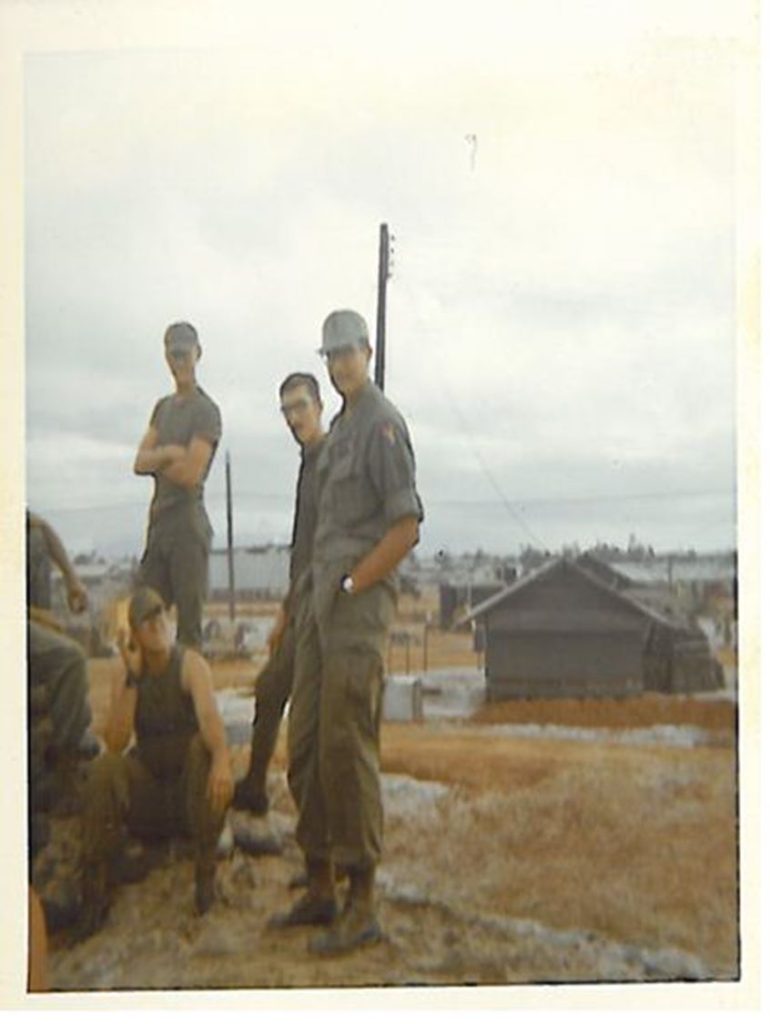

In August of 1971, Gibb arrived in the Republic of South Vietnam. He was sent to the northern part of the country as part of the 101st Airborne Division as a helicopter pilot where his responsibility was to fly around looking for enemy soldiers on the ground to send artillery on them.

“It was extremely dangerous work because we were flying at low speeds and low altitudes. I was shot down three times in a six-month period,” said Gibb. “Finally, the Army could no longer withstand those kinds of losses, so they told me unit to stand down.”

After that Gibb commanded an artillery battery in Da Nang for a short while before flying helicopters again, this time in a different unit close to the demilitarized zone at the 17th parallel in Quang Tri province.

During the Eastern Invasion of 1972, Gibb’s aircraft was hit by antiaircraft missiles leaving him severely wounded spending the next 15 months in the hospital. While recovering from his injuries, Gibb was approached by a recruiter who had worked for the late Henry Ross Perot—businessman, politician, and philanthropist—who at that time owned the second largest brokerage firm in the United States that was exclusively hiring Vietnam veterans. Gibb said he’d consider the offer and was discharged from the Army in August of 1973.

Returning to civilian life was difficult, Gibb shared, joking that “there’s not a lot of civilian demand for field artillery officers, I don’t understand why.” Not having any luck in finding a job, Gibb decided to take the recruiter’s offer and began the journey of becoming a stockbroker.

Gibb graduated from brokerage training in 1974 only to learn that Perot’s firm, DuPont Walston, Inc. was closing after a series of mergers and consecutive months of losses forced the firm into bankruptcy.

Having new specialty training, Gibb was still quick to find work, however, starting his brokerage career at Dean Witter in Paulo Alto, California, then to Morgan Stanley in New York City.

After working at Morgan Stanley, Gibb became partner at Bear Stearns where he began working for Native American communities for which he garnered quite a bit of notoriety—testifying before Congress on Native American issues and helping Native communities sell bonds to finance infrastructure on their reservations. Gibbs assisted in writing more than $3 billion worth of bonds for Native tribes across the country.

While assisting Alaskan native tribes with financial issues during the 1980’s, Gibb would pass through the Seattle area regularly—ultimately falling in the love with the region and deciding to find his own firm in Redmond, Washington, in 1989, called Sweetwater Investments.

Gibb ran Sweetwater Investments for approximately 30 years but during this time he began to abuse alcohol after going through a stressful divorce. Through his firm, he also began committing a Ponzi scheme using his clients’ money to keep his company afloat when times were tough. At the end of the day, Gibb had taken about $4.8 million from his clients.

“I made a lot of stupid decisions which felt right at the time,” said Gibb. “I did not get wealthy off of my crime. I used the money to pay salaries at my firm, and expenses at my firm.”

Gibb’s fraud led him to a five-year federal prison sentence in Sheridan, Oregon on June 28, 2019, at the age of 72. In prison, Gibb worked as the librarian, overseeing over a 10,000-book collection, and from this work, began to form a love for the written word. He began writing down his experiences in the military and working in finance in several compound notebooks to entertain himself.

In 2020, Gibb contracted COVID while in prison becoming deathly ill.

“If you want to transmit an aerial-born disease there’s no better place than a prison,” said Gibb. “We were in an 11 by 16-foot cells with four people. There’s just no way to separate people.”

After Gibb recovered from the coronavirus, the federal public defender’s office in Seattle took his case and applied for him to get a compassionate release, having a high probability of death if he were to contract the virus again.

Strangely enough, on Veterans Day, in 2020, a federal judge in Seattle ruled that Gibb was approved for a compassionate release and he was released from prison on November 25.

The federal government had seized all of Gibb’s property, money, cars, and liquified his assets leaving nothing to his name.

“I was literally dumped on the streets of the International District wearing a gray prison jumpsuit—no phone, no money, no housing,” said Gibb.

Luckily for Gibb the public defender’s office, realizing this was likely to happen, had arranged for someone to pick him up with clothing and transport him to a housing complex in Burien where he began to rebuild his life. His first step was to set up his VA benefits and social security to have an income while taking a job at Goodwill.

“I was fortunate because I was a little older than most folks, I had a better education, I hadn’t been down as long, so I wasn’t institutionalized,” said Gibb.

In 2021, Gibb learned of Edmonds College’s HVRP program—a Department of Labor initiative designed to help veterans who are either incarcerated or homeless to reenter society—which he promptly entered.

“One of the things the prison system and a lot of people don’t think about are the problems people have when they re-enter society from prison,” said Gibb.

In 2023, when the grant that funded the program ended, Gibb was hired as a Navigator for the program to keep it going. Through his position, he contacts every veteran who is in the Department of Corrections custody and walks them through the process of re-entry, while creating a pathway which prevents them from reoffending.

“Over the last few years with the program I’ve had some successes, I’ve also had some notable failures, but it hasn’t been for lack of trying,” said Gibb. “There is a tremendous network of services to provide help for people, especially veterans, who are coming out of prison. The problem is that they’re scattered all over the place, so accessing them is very difficult for people. Imagine you’ve been locked in a cell for 15 years and you come out, do you call Workforce, WorkFirst, or WorkSource? The state legislatures don’t know either.”

The answer to Gibb’s question is WorkSource but for those who mistakenly make the wrong call they might be shrugged off completely, he added.

“What I realized is that these people need is a navigator who, if necessary, will literally take them by the hand and walk them to the right people,” said Gibb.

Edmonds College’s HVRP Program provides job placement, all kinds of support for those having difficulty reentering an education environment, its own food pantry, emergency financial grants to assist people when needed, representatives from WorkSource and other places.

Representative Cindy Ryu (D-Shoreline) sponsored a bill this legislative session, HB 2057, that would have supported this program for five more years and added another Navigator in Eastern Washington. The bill did not move out of committee for the 2024 Legislative Session.

“Every year about 140 or so veterans who are incarcerated are rereleased back into society after paying for their crimes,” said Rep. Ryu during her virtual Town Hall in February. “Fortunately, Edmonds College has a program that connects with them, I believe, six months before they’re released, so they are getting the help they need to make sure they continue education as well as access housing. I wanted to make sure this program continues and, hopefully, expands.”

Ryu said during the 32nd Legislative District virtual Town Hall that she plans to continue working on the bill through the interim to bring it back to the table next session.

In addition to his working as Navigator for Edmonds College’s HVRP Program, Gibb is an author of several books including his first novel Exordium, which is what eventually became of the journals he wrote in prison.

His latest novel, An Da Shelladh, is about Scotch-Irish people with a psychic ability to predict the future living in the 21st century—a world dominated by science, reason, and facts. An Da Shelladh was published in January 2024 and is available for purchase on Barnes and Noble. It was featured under the New Author section at the London Book Fair in March and will be featured at the American Library Association this June.

All the profits Gibb makes from his book sales go towards paying back a $1.8 million federal restitution from the crimes he committed at his firm. He shared with the Lynnwood Times that he is determined to pay “every dollar back.”

RELATED ARTICLE

Author: Kienan Briscoe