EVERETT—A Lynnwood Times study of National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) incident records from 2014 to 2023 concludes that there is no statistically significant safety difference between US-related Boeing and Airbus commercial aircraft.

Boeing scrutiny and oversight

After Alaska Airlines Flight 1282’s non-fatal incident involving a cabin door blowing off mid-flight on January 5, 2024, due to four key bolts missing, according to a preliminary report from the NTSB, Boeing has been under intense scrutiny by federal regulators and media.

The incident resulted in the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) temporarily grounding, for weeks, similarly configured Boeing 737 Max 9 aircraft to undergo inspections. The action by the FAA was reminiscent of the March 2019 grounding of all Boeing 737-MAX aircraft shortly after Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302, a 737-MAX 8 aircraft, crashed six minutes after takeoff from Addis Adaba killing all 157 people aboard. Just months earlier, on October 29, 2018, Lion Air Flight 610 crashed into the Java Sea 12 minutes after takeoff, killing all 189 passengers and crew. Both 737-MAX 8 aircraft, and the Boeing 737 Max 9, were only a few months old at the time of their incidents.

On March 4, 2024, the FAA “halted production expansion of the Boeing 737 MAX,” as a financial incentive for the company to address what the FAA calls, “production quality issues.” A six-week FAA audit of the Boeing 737 Max 9 production line found multiple “manufacturing process control, parts handling and storage, and product control” problems. Regulators also required the aircraft manufacturer to develop a comprehensive plan within 90 days to address the “systemic quality-control issues.”

On Thursday, May 30, the FAA accepted Boeing’s comprehensive “Product Safety and Quality Plan,” that aims to tighten supplier oversite and manufacturing processes.

On March 25, Boeing’s President and CEO Dave Calhoun, along with BCA president and board chair, announce their resignations. A month later, on April 25, S&P Global downgraded Boeing from “stable” to “negative” a day after Moody’s similar announcement.

“The company faces heightened production uncertainty, notably related to quality issues affecting its 737 MAX aircraft, and key changes to its leadership are pending,” the report reads. “We revised the rating outlook to negative from stable and affirmed our ‘BBB-‘ long- and ‘A-3’ short-term issuer credit ratings on the aerospace and defense company.”

S&P Global expects Boeing to have poor “cash flow and credit ratios” due to the risk of “further delays” related to the company’s commercial aircraft production.

NTSB incident data deep dive

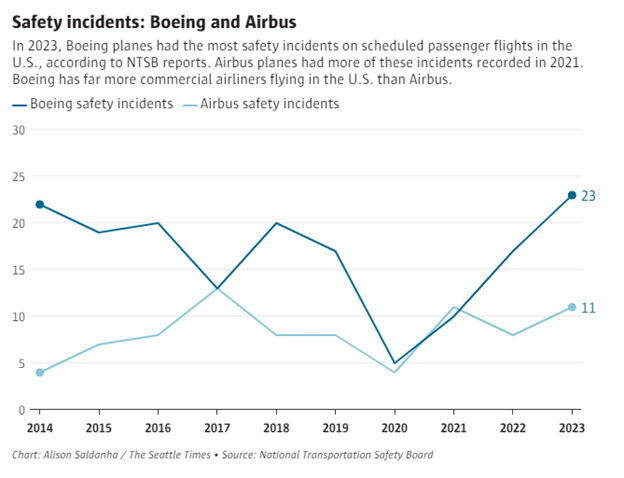

Almost daily, so far this year, there are reports of safety incidents involving a Boeing manufactured plane in the news. Recently, the Seattle Times published a well-researched article comparing the safety record of Boeing-built aircraft to that of its primary competitor, Airbus, using NTSB data—see below.

At first glance it appears that Airbus, with its 82 incidents to Boeing’s 166, is a much safer aircraft to fly. The Lynnwood Times was able to duplicate similar results from the NTSB database but with 170 reported incidents over the last 10 years for Boeing. Because both aircraft models have varying scales, displaying only the aggregate of the data—not normalized—as presented by the Seattle Times may lead to possible misinterpretation of its findings.

Performing a One-Way ANOVA analysis, a statistical test used to evaluate the difference between the means datasets, indicated that there is strong evidence (p-value 0.00058) with a 95% confidence level that Airbus safety incidents differ by 8.4 per year, well beyond any likelihood of being statistically equal. The mean for Airbus yielded 8.2 [±2.898] incidents and 16.6 [±5.680] for Boeing. In other words, the way the data is presented by the Seattle Times, allows for the misinterpretation that Airbus aircraft is much safer than Boeing-built aircraft.

When analyzing data of varying scales, it must be adjusted to a notionally common scale, in this case million departures per year and million block hours per year—an apples-to-apples comparison. Boeing has almost 60 percent more departures within the United States than Airbus and just over 40 percent more commercial block hours (duration of passenger revenue service). What this means is that there are more opportunities for a Boeing aircraft to experience a safety incident in the U.S. than an Airbus aircraft. Therefore, the data must be normalized to a common scale.

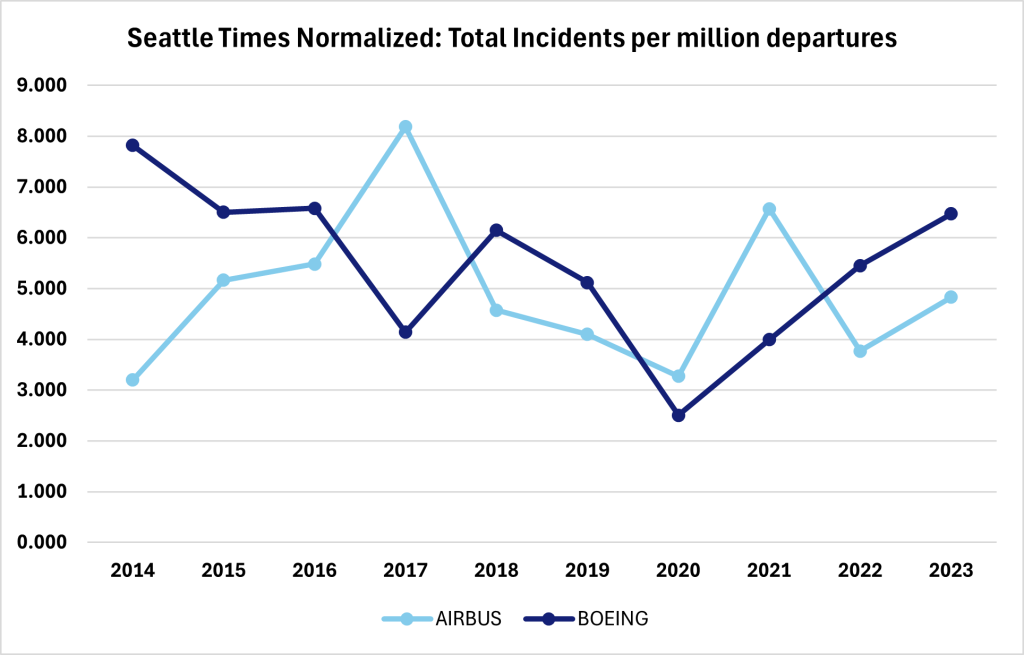

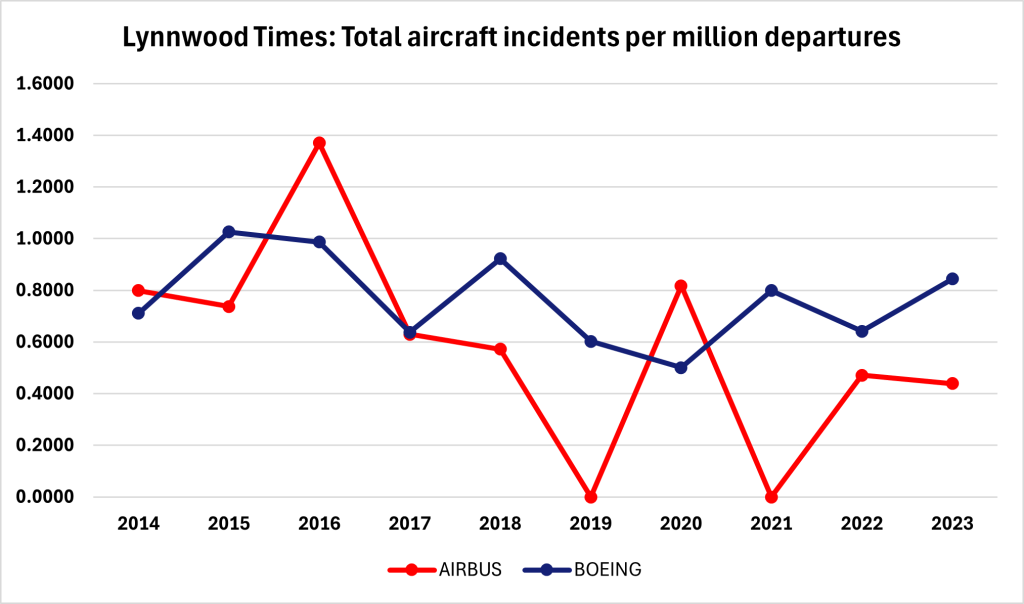

Below are normalized charts of all reported commercial incidents using the data from both the Seattle Times (normalized by the Lynnwood Times) and Lynnwood Times. Using a million block hours per year generated similar charts and same conclusion from the statistical analysis. For simplicity, only charts showing million departures per year are displayed for a one-to-one comparison.

Normalizing the safety data presented by Seattle Times tells a much more accurate story. Just with a visual look, the two datasets appear similar.

A One-Way ANOVA analysis for the above chart indicates there is strong evidence (p-value 0.4337) with a 95% confidence level that the means of Airbus and Boeing safety incidents do not differ significantly. The mean for Airbus yielded 4.9136 [±1.5491] incidents per million departures per year and 5.4718 [±1.5681] incidents per million departures per year for Boeing.

In other words, you are as likely to experience a safety incident with Boeing as with Airbus. However, keep in mind that these are all reported safety incidents, treating minor coffee spills with the same level of severity as an engine failure.

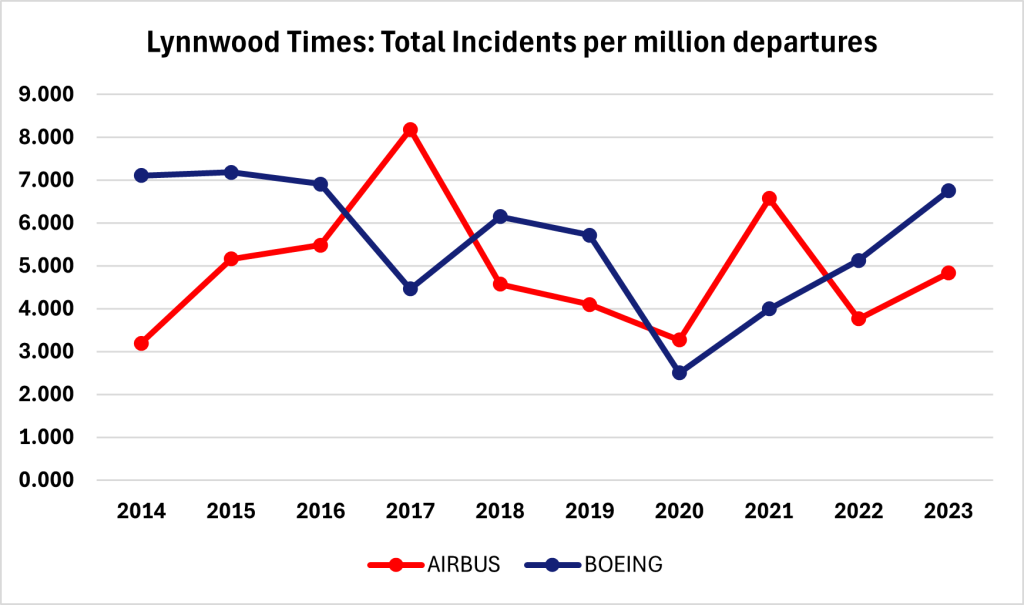

Performing the One-Way ANOVA analysis for all incident data using the Lynnwood Times dataset also yielded strong evidence (p-value 0.3429) with a 95% confidence level that the means of Airbus and Boeing safety incidents do not differ significantly. The mean for Airbus yielded 4.9136 [±1.5491] incidents per million departures per year and 5.5901 [±1.5570] incidents per million departures per year for Boeing.

Although the Lynnwood Times’ dataset yielded a slightly lesser significance value, it is still statistically sound. Also, both the means for the Lynnwood Times and the Seattle Times differs for Boeing by 0.1183 (just over 2 percent).

In his article, “Does data show Boeing is unsafe?,” by Courtney Miller, Founder and Managing Director, Visual Approach Analytics, he pointed out the Seattle Times’ use of “aggregate numbers of incidents” suggests to the reader that Boeing’s safety incident rate “is higher” than Airbus contrary to the data.

“The Seattle Times did an admirable job of providing more context to the NTSB numbers in a recent article,” wrote Miller. “You’ll notice very similar-looking charts to ours, but with one key difference: aggregate numbers of incidents are still used [by Seattle Times], suggesting Boeing’s rate is higher while providing the context of greater Boeing departures separately in the text.”

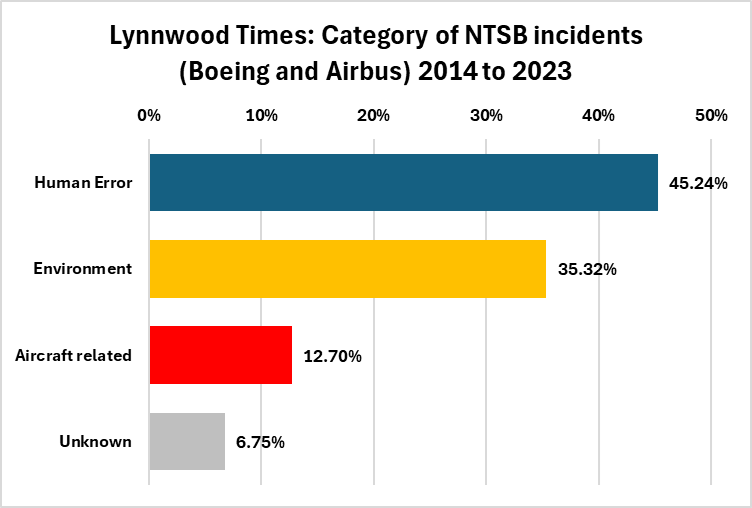

The Lynnwood Times took Miller’s lead from his article and reviewed all 319 reported aircraft incidents for both Boeing and Airbus from 2014 to 2023. Cargo and general aviation (charter and biplanes) built by the two aircraft manufacturers were removed because one cannot accurately estimate the number of flights and hours. The remaining 252 reports were then categorized as unknown, environmental factors, human factors, and aircraft related.

Miller’s dataset differed slightly in that it had 165 Boeing (five less than Lynnwood Times) incidents and 84 (two more that Lynnwood Times) Airbus incidents.

Not all reported incidents have the same level of severity. The NTSB database includes all reported US-related accidents and incidents—from a coffee spill resulting in an injury to a fatal plane crash. The data shows that 80.56 percent of incidents are Human and Environmental factors, and only 12.7 percent are aircraft related.

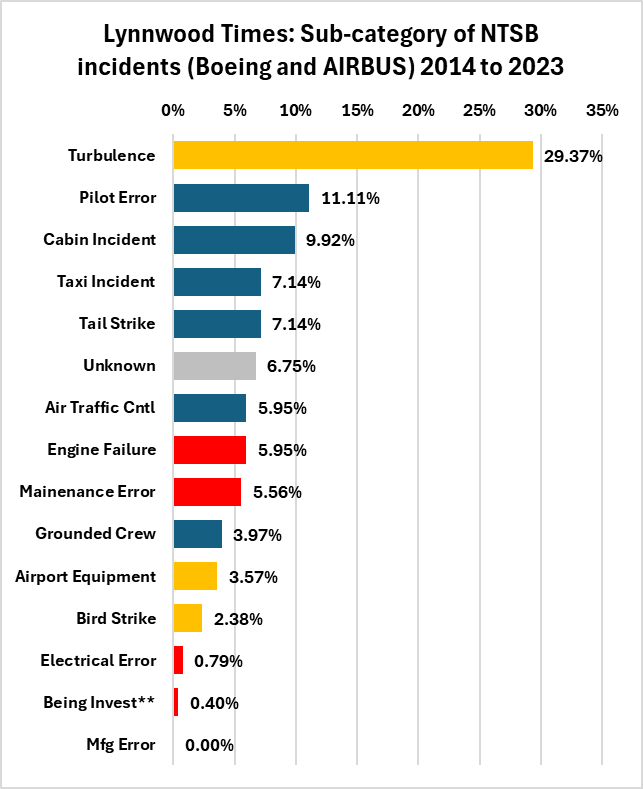

Human factor incidents were subcategorized as pilot error, cabin incident, taxi incident, tail strike (which one incident was weather related), air traffic controller error, and grounded crew. Environmental factor incidents were subcategorized as turbulence, airport equipment, and bird strikes. Aircraft related incidents were subcategorized as aircraft manufacturer, electrical, engine failure, and maintenance error (can also be considered a human factor).

The most common incident reported was turbulence at 29.37 percent, followed by pilot error and a cabin incident (spilled coffee or cart injury). Almost all injuries were related to turbulence, cabin, or grounded crew incidents. Both Boeing and Airbus had no manufacturing incidents reported in the NTSB database for U.S. related flights during this period.

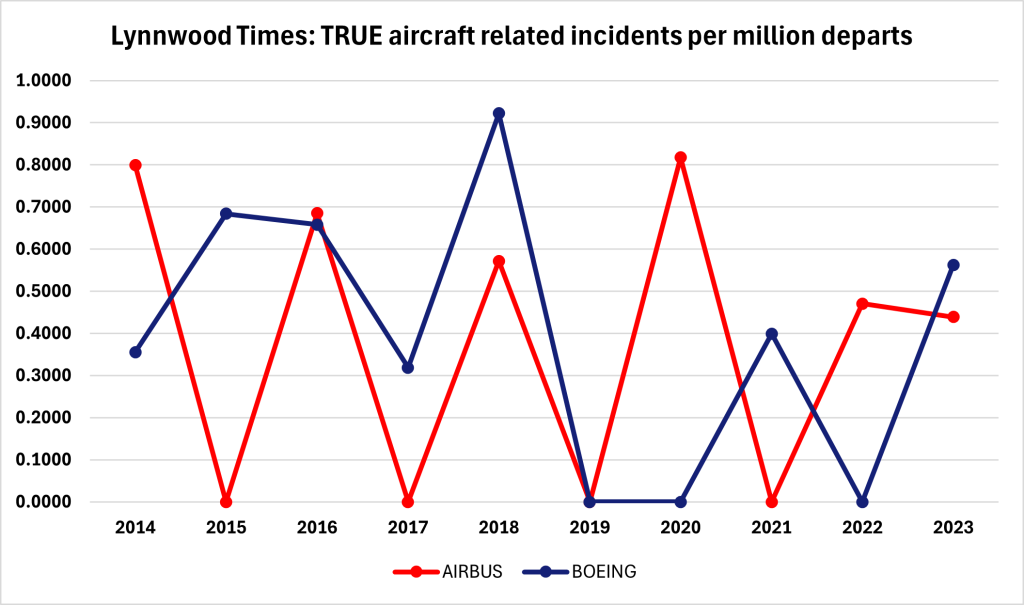

A One-Way ANOVA analysis for all aircraft related (including maintenance) incident data using the Lynnwood Times dataset yielded somewhat strong evidence (p-value 0.2041) with a 95% confidence level that the means of Airbus and Boeing aircraft related safety (including maintenance) incidents do not differ significantly. The mean for Airbus yielded 0.5836 [±0.4030] incidents per million departures per year and 0.7669 [±0.1765] incidents per million departures per year for Boeing.

The Boeing aircraft related safety data is tighter to its mean, whereas Airbus’ occurrences have a greater variance. In other words, Boeing aircraft related safety is consistent for this dataset.

Removing the “noise” from the data by focusing on all aircraft safety, including maintenance incidents, (not those due to human and environmental factors) provides a more accurate story for what is in the control of the aircraft manufacturer.

When comparing aircraft related incidents with maintenance and without maintenance in the dataset, the number of Boeing and Airbus incidents per million departures dropped 49 and 35 percent respectively. This significant reduction conveys the importance of routine maintenance by an airliner for the prevention of a safety incident.

The aircraft safety data with maintenance related incidents removed from the aircraft related category more accurately reflects aircraft-only incidents, as maintenance truly is attributed to human error and is the responsibility of the airline (e.g. United, Alaska, Delta, etc.) maintenance personnel or third-party maintenance personnel and not the aircraft manufacturer.

Performing a One-Way ANOVA analysis for true aircraft related (not including maintenance) incident data using the Lynnwood Times dataset yielded very strong evidence (p-value 0.939) with a 95% confidence level that the means of Airbus and Boeing’s true aircraft related safety incidents do not differ significantly. The mean for Airbus yielded 0.3784 [±0.3475] incidents per million departures per year and 0.3900 [±0.3221] incidents per million departures per year for Boeing. In other words, Boeing’s true aircraft related safety is almost identical to that of Airbus from 2014 through 2023.

For the last ten years, Boeing has averaged 5.5901 incidents per million departures and Airbus has averaged 4.9136 incidents per million departures, regardless of incident severity. However, because of the variability in incidents per year, the overall safety for both aircraft manufacturers is statistically the same.

For true aircraft related incidents, removing maintenance caused, the average over ten years drops to 0.3900 and 0.3784 incidents per million departures for Boeing and Airbus respectively. Again, statistically when factoring variability, these are the same.

Although our numbers differed slightly, the analysis by Visual Approach Analytics also concluded that the true aircraft related safety rates for both aircraft manufacturers, Boeing and Airbus, are in fact the same.

“Even though the [Seattle Times] article aimed to quell the same misinformation, the charts still show elevated Boeing incidents when, in fact, the rate is the same,” wrote Miller. “A seemingly small difference to us, but consider this article was sent to me by a concerned family member who used it to ‘prove’ that Boeing aircraft were unsafe. The attempt by the Seattle Times to use good data to ease irrational fears actually added to the hysteria in this anecdote.”

Why the regulatory and media hype

It begs to question, when the empirical data is easily available, why regulators are not requiring, and the media not reporting, the same level of “scrutiny” for Airbus.

Each day, about 2.9 million people fly on commercial aircraft in the United States. The last fatal U.S. crash of a commercial airliner was Continental Flight 3407 in January of 2009, killing 49 passengers and crew, and one person on the ground. From 2010 to 2022, eight people, according to the NTSB, have died using commercial airlines. General Aviation, which are small and experimental planes, saw 4,079 fatalities during that same period.

According to the Washington State Traffic Safety Commission, there were 810 traffic fatalities in 2023, up 9 percent from the previous year. This equates to 102 fatalities per million people or 2.22 fatalities per day within the state. The commission reports 429.2 serious traffic injuries per million people in Washington state for 2023 or 9.35 people per day.

US commercial air travel, in comparison, for the last 15 years has reported 0.00146 fatalities per day, and according to the NTSB’s Railroad Passenger Safety Data statistics, from 2009 to 2023, there were 76 fatalities across the U.S. or 0.0139 fatalities per day for commuter rail.

However, since the Alaska Airlines incident in January, news outlets appear to be relentless in their coverage of airplane incidents, specifically those that involve Boeing, to the point where Kayak.com is experiencing a spike from travelers filtering out Boeing planes out of fear.

A recent Vox article sums up the media hype best: “Their [travelers] fears have been fueled by news sites that have been serving up incident after incident: a Boeing 737 Max 8 sliding off the runway in Houston, another 737 in Houston making an emergency return after flames were spotted spewing out of an engine, yet another in Newark reporting stuck rudder pedals, a Boeing 777 losing a tire shortly after takeoff from San Francisco, a 777 making an emergency landing in Los Angeles with a suspected mechanical issue. And so on and so on.”

The Qatar Airways incident last week that injured 12 due to turbulence enroute from Doha to Dublin read on Fox Business, “12 Qatar Airways passengers injured as Boeing jet hits turbulence en route to Dublin,” with the byline, “Passengers say episode on Boeing 787-9 Dreamliner traveling from Doha to Ireland was ‘scary.’”

Fox Business in March reported that travelers are resulting to medication and prayer when flying because of the hype.

“If you start with a conclusion, you can always find some data to support it,” Courtney Miller, Founder and Managing Director, Visual Approach Analytics, told the Lynnwood Times in a statement. “In this case, it seemed logical that Boeing aircraft were less safe than Airbus because of all the negative coverage on Boeing. But the data simply doesn’t support that conclusion. The United States shows more Boeing incidents because Boeing is a U.S. manufacturer and all Boeing incidents around the world are reported. Conversely, France shows more Airbus incidents because of the same dynamic. In the end, both Boeing and Airbus aircraft have incredibly similar incident rates – and both are infinitesimal. Both Boeing and Airbus aircraft are extraordinarily safe to fly.”

Year-to-date there are 12 reported Boeing incidents to Airbus’ one. However, as of June 4, 2023, there were eight reported Boeing incidents. Seven of the 12 incidents this year have reported injuries, but the probable cause has yet to be determined. Based off historical data, these are most likely going to be classified as turbulence, cabin, or ground incident—non-aircraft related—except for the Alaska Airlines incident in January.

Why Boeing’s woes may become your problem

In 2020 when Boeing halted its production of the 737 MAX, economists estimated a 0.5- to 0.6-percent drop in GDP growth for the entire U.S.

Boeing’s stock is down 27.2 percent since January 2, 2024, from $258.59 to $188.30 as of June 4. With S&P Global and Moody’s lowering the aircraft manufacturer’s creditworthiness in April, the FAA capping 737 Max production to 38 planes per month, delays in 777X production, and setbacks meeting mandated international “greener” emission standards for its 767 aircrafts, the company may soon face a cash crunch as it burns through billions of dollars more than projected.

Boeing Chief Financial Officer Brian West warned investors at a conference in May that the company is set to lose at least $3.9 billion in its second quarter matching the previous quarter’s lost. Boeing’s cash on hand for the quarter ending March 31, 2024, was $7.52 billion according to its financial quarterly report. A positive is that the company had a $529 billion backlog.

Boeing is one the nation’s largest exporters and has a global workforce of 170,000 with approximately 66,000 employed in Washington state. It has contracts with at least 12,000 suppliers around the world of which over 1,000 are in Washington state.

Aerospace is a $70 billion industry in Washington state employing some 130,000 according to the Washington State Department of Commerce. In 2022, Boeing paid more than $200 million in taxes to Washington state.

America’s number one aircraft manufacturer is in a race against time to implement more robust quality controls, to the FAA’s liking, and repair its public image.

Boeing has faced challenges in the past, such as the fatal Lion Air and Ethiopian Airlines incidents, and the 787 aircraft lithium-ion battery debacle. The company of innovators and hard-working union employees in the Puget Sound area, always “find a way” to do the impossible and succeed.

Author: Mario Lotmore

6 Responses

Boeing has more scrutiny due to the nature of some of the problems.

The MAX losses were due to a fundamental design error implemented to save costs over a proper solution to the issue and the failure to adequately disclose what had been done and what issues needed to be addressed. Boeing’s chief tech pilot took credit for his Jehdi Mind Tricks having gotten the system approve with limited disclosure to the customers ( it was removed from the Pilot handbook to avoid the need for sim training)

The loss of the door was a HUGE RED FLAG that inspections were not being properly accomplished and the there were procedural issues. The absence of the bolts was so easy to detect that there was no question that it was never inspected prior to covering.

For the FAA and politicians it was a blinking red light that they were at risk … and that there were serious problem

The 737 max. Accidents were clearly a design error with large numbers of fatality. Their statistics were lost in the noise. Suggest to focus on things we can easily do: pilot errors and training, design errors and corrective action/lessons learned.

“The last fatal U.S. crash of a commercial airliner was Continental Flight 3407 in January of 2009, killing 49 passengers and crew”

What about Asiana Airlines Flight 214 on July 2013 when 3 people died when the airplane crashed at SFO? How does this not count as a fatal crash?

Are any of these airplanes outfitted with small parachutes in the event passengers and crew might have some to escape realizing the flight is going to crash?

Mate parachutes require training to use properly, add excessive amounts of weight, and are expensive.

need to publish data again by consider Boing 787 Case happened in India