The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) on October 30, released its findings that the Antarctic ozone hole that opens up annually over Antarctica is now relatively small in 2024 compared to other years. NOAA and NASA scientists project the ozone layer could fully recover by 2066.

During the peak of ozone depletion season from September 7 through October 13, the 2024 area of the ozone hole ranked the seventh-smallest since recovery began in 1992. That’s when the Montreal Protocol, a landmark international agreement to phase out ozone-depleting chemicals, started to take effect.

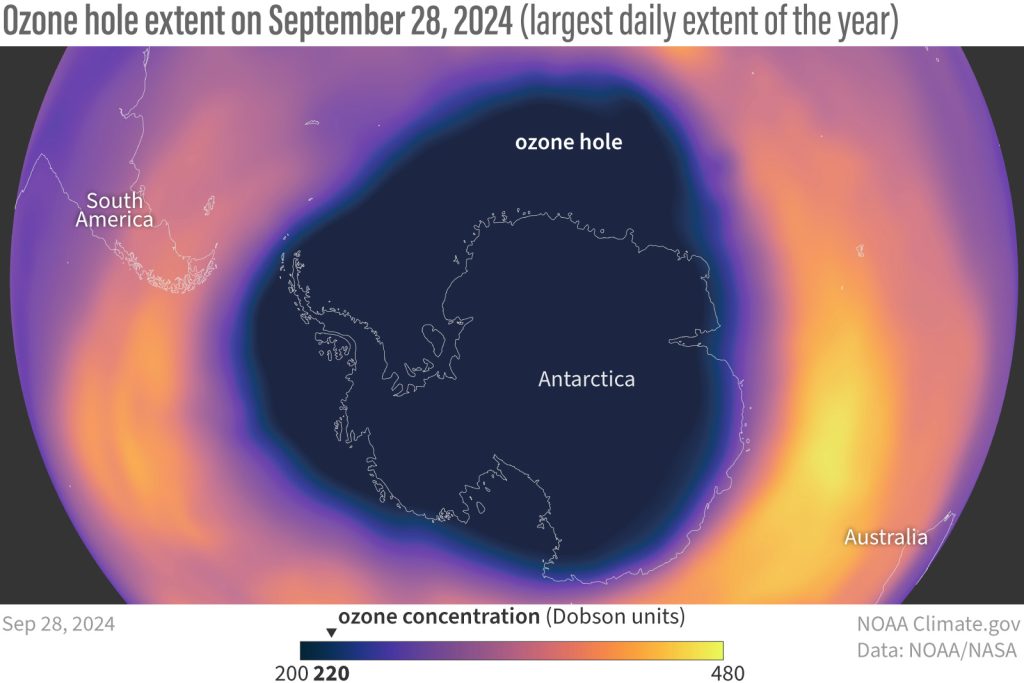

At almost 8 million square miles (20 million square kilometers), the monthly average ozone-depleted region in the Antarctic this year was nearly three times the size of the contiguous U.S. The hole reached its greatest one-day extent for the year on September 28 at 8.5 million square miles (22.4 million square kilometers).

The improvement this year is due to a combination of continuing declines in chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), an ozone-depleting chemical phased out by the Montreal Protocol, along with an unexpected infusion of ozone carried by air currents from north of the Antarctic, scientists said.

“The 2024 Antarctic hole is smaller than ozone holes seen in the early 2000s,” said Paul Newman, leader of NASA’s ozone research team and chief scientist for Earth sciences at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “The gradual improvement we’ve seen in the past two decades shows that international efforts that curbed ozone-destroying chemicals are working.”

In previous years, NOAA and NASA have reported the ozone hole ranking using a time period dating back to 1979, when scientists started tracking Antarctic ozone levels with satellite data. Using that longer record, which includes the years prior to recovery spurred by the Montreal Protocol, this year’s hole ranked 20th-smallest in area across 45 years of observations.

The ozone-rich layer high in the atmosphere acts as a planetary sunscreen that helps shield us from harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun. Areas with depleted ozone allow more UV radiation through, resulting in increased cases of skin cancer and cataracts. Excessive exposure to UV light can also reduce agricultural yields as well as damage aquatic plants and animals in vital ecosystems.

Scientists were alarmed in the 1970s at the prospect that chlorofluorocarbon (CFC) chemicals could eat away at atmospheric ozone. By the mid-1980s, the ozone layer had been depleted so much that a broad swath of the Antarctic stratosphere was essentially devoid of ozone by early October each year. Sources of damaging CFCs included coolants in refrigerators and air conditioners, as well as aerosols in hairspray, antiperspirant and spray paint. CFCs were also released in the manufacture of insulating foams and as components of industrial fire suppression systems.

The Montreal Protocol was signed in 1987 to phase out CFC-based products and processes. Countries worldwide agreed to replace the chemicals with more environmentally-friendly alternatives by 2010. The release of CFC compounds has dramatically decreased due to the Montreal Protocol. But CFCs already in the air will take many decades to break down. As existing CFC levels gradually decline, ozone in the upper atmosphere will rebound globally, and ozone holes will shrink.

“For 2024, we can see that the ozone hole’s severity is below average compared to other years in the past three decades, but the ozone layer is still far from being fully healed,” said Stephen Montzka, senior scientist with NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory.

Scientists expect atmospheric ozone to return to levels that eliminate holes over the poles in the second half of this century.

Researchers rely on a combination of systems to monitor the ozone layer. They include instruments on NASA’s Aura satellite, and NOAA’s polar orbiting satellites: The NOAA-20 and NOAA-21 satellites and the Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership satellite, jointly operated by NOAA and NASA.

NOAA scientists also release instrumented weather balloons from the South Pole Baseline Atmospheric Observatory to observe ozone concentrations directly overhead in a measurement called Dobson Units. The 2024 concentration reached its lowest value of 109 Dobson Units on October 5. The lowest value ever recorded over the South Pole was 92 Dobson Units in October 2006.

NASA and NOAA satellite observations of ozone concentrations cover the entire ozone hole, which can produce a slightly smaller value for the lowest Dobson Unit measurement.

“This is well below the 225 Dobson Units that was typical of the ozone cover above the Antarctic in 1979,” said NOAA Research Chemist Bryan Johnson. “So, there’s still a long way to go before atmospheric ozone is back to the levels before the advent of widespread CFC pollution.”

SOURCE: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

Author: Lynnwood Times Staff