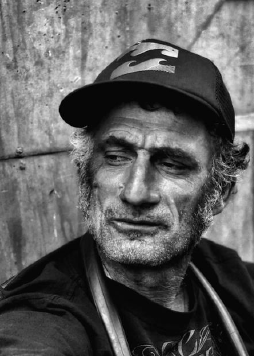

At hour 30 in the emergency room, Daniel, Navy veteran, former submarine engineer, asks through his psychosis, “Am I a good person?” When crisis responders finally call his name, I already know what happens next. Thirty-day stay. Insurance runs out. Discharge to street. No plan.

I know because I’ve spent a year conducting 598 interviews throughout King and Snohomish homelessness ecosystem. What I discovered: a $200 million machine that counts bodies, not souls. A system so fragmented that emergency services, treatment facilities, and housing programs operate in total isolation from each other.

This isn’t about homelessness. It’s about how we built a machine that manufactures human misery, then profits from managing it.

The Black Box

Fifty agencies. Fifty databases that don’t communicate. All scrambling for 128 funding sources while four organizations swallow most of the pie. Emily, 23, arrives at the ER in psychosis. That information stays trapped. HIPAA, meant to protect her, becomes the wall that kills her. Her father can’t access information that could save her life. “The privacy laws protected her right to die alone,” he tells me.

Three miles away, a treatment bed sits empty. The facility doesn’t know she exists. She doesn’t know it exists. The databases don’t talk.

She’s found naked, murdered in Seattle the next day. “HIPAA was her death sentence,” her father said. “They gave her the privacy to die but not the family to live.”

Warehouse Deaths

“They’re mixing fentanyl with oven cleaner now,” Mike Kersey tells me. After three decades in addiction recovery, first saving his own life, then countless others, he co-founded Courage to Change with Christina Anderson to combat an epidemic that keeps finding deadlier forms.

Walk past any “Housing First” building and look up. See the photos taped to windows. “Ten ODs, five deaths in one week,” reports one resident of East Lake, Seattle’s flagship Housing First complex. We imported the Housing First model from New York, celebrated by Finland’s success, but stripped away the wraparound services that made it work. What remains are warehouses of neglect, where people die alone behind doors that staff rarely check, their only memorial a photograph pressed against glass.

At 2:47 AM, Leslie’s phone rings. Another overdose. As former DESC Building case manager, she fought for real solutions, demanded medical interventions, pushed for mental health assessments. She had to leave because DESC demanded paperwork for funding rather than connection. “You care too much,” they said. “You’re not following protocol.” The protocol: document occupancy for funding, not outcomes. Dead or alive, they’re “housed,” funding secured.

Now she answers crisis calls on her personal phone, prohibited to enter, her clients in desperation. DESC considers her care as a threat to their model. Leslie counts them as murdered by indifference. Funding secured, the machine grinds on.

The Missing Millions

In 2008, Snohomish County instituted the chemical dependency and mental health sales tax to help solve these problems. The Human Services report to County Council for last quarter shows that they allocated $1.378 million for “contract managers,” $638,774 for “1.9 FTE evaluators” despite there not being an unbiased evaluation report done on any of the programs since 2016. The evaluator reports directly to the person controlling all Human Services funding, a textbook conflict of interest that ensures positive reviews regardless of actual outcomes. When the person grading your performance signs your paycheck, failure becomes impossible to document. For the 25/26 fiscal year, how does the County account for $638,774 being spent in tax dollars on less than two evaluation positions especially when no reports or evaluation of the CDMH funded programs is happening? How does the County account for over $2,000,000 for Human Services overhead?

The Carnegie Center, which has no documented outcomes at all, received $2.9 million of this sales tax last year. The Human Services director at the June CDMH board meeting claimed 7,000 people served by the Carnegie Center but when pressed whether these were unduplicated individuals or repeat visits, the real number emerged: 500. Nobody was able to say exactly what outcomes were achieved for these people or what services they had received. Meanwhile, HopeNWellness, where people actually recover, faces closure over zoning violations and lack of funding. Despite millions of CDMH dollars being spent on administrative tasks at the County, agencies trying to help the community are often going without.

At LEAD, an employee who feared retribution whispered the truth: “We’ve had the same data-sharing meeting every quarter for 14 years with the county. Same PowerPoints. Same promises. We burn $50,000 annually on software contracts that can’t communicate across data silos. Fourteen years of meetings about connecting systems while people die in the gaps between them. Nothing changes except the body count.”

The system captures every arrest, overdose, ER visit, documenting how trauma screams through broken bodies while the person disappears into databases that protect budgets, not people. We’ve built a machine that ignores trauma, recognizes people only by their symptoms, feeds on failures while treatment beds sit empty.

The Trauma Nobody Sees

92% of homeless women in Everett report sexual abuse histories. When trafficking survivor Luz arrives at 3 AM, bruised, holding her daughter, the nurse documents injuries into a void. The trafficking program down the road has beds available. They’ll never know she exists, and she is too afraid to call.

“The brain built in violence becomes condition to chaos, addicted to tension that inhibits the human from any real connection” Frank Grijalva MSCC, MSPH reveals. “When your neural pathways were carved by fear instead of love, you don’t just struggle to recognize healthy relationships, you’re magnetically drawn to what destroys you. Your capacity for connection has been hijacked. Your survival instincts remain intact but operate in isolation. What should signal alarm feels familiar.”

This is the predator’s blueprint: They don’t hunt the strong. They hunt the wounded whose nervous systems broadcast vulnerability and interpret exploitation as intimacy. Whose bodies learned that love comes with a price, whose minds were trained that care always carries threat. They find those whose internal warning systems were disabled in childhood, those who run toward the very thing that will devour them because destruction is the only touch they’ve ever known.”

Dave, five years clean: “They handed out Oxycontin like candy after surgery. When prescriptions stopped, the pain didn’t.” His journey from Boeing employee to street addict illuminates what the system ignores: addiction isn’t moral failing, it’s survival strategy for unbearable pain.

Yet we offer 28-day detox for lifetime trauma. Discharge people to corners where dealers wait, pimps circle. Call it “treatment resistance” when someone relapses the ninth time, ignoring we returned them to the environment that created the addiction.

What Works and Why We Kill It

We know coordination saves lives. Everett’s CHART program proved it in 2016. The Chronic High Utilizer Alternative Response Team program was created specifically to address in a compassionate way the needs of those most vulnerable in our community. After just one year, they found that for six chronic utilizers there were not only improvements for the people in the program but also for the taxpayers as a whole. Results: 80.6% reduction in EMS contacts, 92% reduction in jail days, $143,450 saved in hospital charges.

If you watch the YouTube video below on the Everett Safe Streets, you get more detail from the people who created the program.

“Homelessness affects the entire community” says Julie Zarn, the former director of emergency services for Providence, Everett. People are coming into the emergency department since they have nowhere else to go. “At the jail, we were seeing an influx of people on specialty housing, people coming in on Oxy, people coming in with mental health issues. They were there on minor charges. My issues coincided with CHART issues and that was, we needed to find a solution,” says Anthony Aston, former Bureau Chief of Corrections for the Snohomish County Jail. “Wedefinitely want people to get the help that they need,” said Dr. Robin Fenn, former research manager for Snohomish County Human Services. “But while we are doing that, we need to take a look at the impacts to the system. When we start just pushing the money back and forth across the systems, we aren’t doing anybody any favors.”

I tried finding out what happened to the CHART program. CHART died. Not from failure, from success. Staff turnover and “lack of institutional mandate” killed a program transforming lives. The machine doesn’t want solutions. It wants problems to manage. CHART was breaking down silos, forging unprecedented partnerships, like the Lynnwood Jail and Community Health Center building a clinic inside the jail. Months of collaboration. Tax dollars saved. Healthcare access expanded. They even built out the space during remodel. Then malpractice insurance and federal bureaucracy killed it. A fully constructed clinic sits empty while inmates go without care and taxpayers’ foot bigger bills.

This is how innovation dies, not in flames, but drowning in paperwork. CHART didn’t just coordinate services; it exposed the lie that our institutions want coordination. They want their fiefdoms. They want their budgets. They want problems that justify next year’s funding, not solutions that might reduce it.

The Choice

Tomorrow, Daniel wakes on concrete, his brilliant mind cataloging his dissolution. Fairfax Psychiatric Hospital just released him after 30 days, stabilized him enough to remember what he’s lost, then discharged him to the street with a garbage bag of prescriptions. “Take these three times daily,” some doctor wrote, signing what amounts to a death sentence. The pills will last two weeks. His psychosis will return in three.

His DOC officer doesn’t know where he is. The databases don’t talk, remember? Daniel shuffles back to Courage to Change’s door, clutching discharge papers no one will read. Mike looks at him with knowing despair, CTC runs on donations and recovered addicts’ sweat equity. They’re not equipped for acute psychosis, for the nuclear engineer whose mind splits between submarine calculations and CIA conspiracies. They’ll give him coffee, not the intensive psychiatric intervention he needs.

“We can’t take him,” Mike tells me quietly. “He needs 24/7 medical supervision, trauma therapy, medication management. We’re addicts helping addicts. This is beyond us.” But where else can Daniel go? The system offers no middle ground between psychiatric lockdown and street abandonment.

So, we’ll spend $100,000 cycling him through emergency rooms, police interventions, brief hospitalizations that end the same way, discharge to nowhere with pills that run out before the next appointment he’ll never make. We could house him with wraparound psychiatric care for roughly $30,000 yearly. Instead, we’ve signed his death warrant with prescriptions and indifference.

Cities spend more than $87,000 annually jailing someone when $12,000 could provide the trauma inform support needed. 771,480 Americans experienced the trauma of homelessness in 2024, highest ever recorded. Five deaths happened last week in single Housing First buildings in Seattle. Photos multiplying on windows. Daniel’s will join them soon.

The path forward: Connect databases so emergency rooms know who to contact to support the next homeless patient, so case managers can find their clients before they overdose, families can advocate before it’s too late, and treatment facilities can reach people while they’re still alive. End the black box that turns humans into scattered data points no one can piece together until the autopsy.

Track real outcomes beyond “discharged stable,” or “housed successfully.” Fund intensive interventions, not pharmaceutical Band-Aids. Treat trauma, not just symptoms. But in a system where Fairfax gets paid per admission, not per life saved, where failure is profitable and success threatens funding streams, competence becomes revolutionary.

“I just want to be good again,” Daniel told me between explanations of submarine engineering, clutching his two-week supply of sanity.

The machine has signed his death warrant. Daniel dies from our compliance. Every activist screaming “choice” while watching him shoot poison into his veins is complicit. Every policy that prioritizes his “right” to die in the street over his chance to heal is murder disguised as compassion.

We’ve given the addiction a voice. We’ve given the psychosis autonomy. We’ve given the trauma voting rights. And they all vote for death.

Daniel, the engineer, the father, the human being, hasn’t had a voice in years. His disease speaks for him now, and we nod along, calling it “dignity” while he rots on concrete. This isn’t harm reduction. It’s harm worship.

Stop giving trauma a voice. Start giving humans treatment. Stop documenting deaths in the name of choice. Start preventing them in the name of life.

The system is corrupt and broken, and we know it. Daniel knows it too, in his rare moments of clarity when the real him surfaces, gasping: “I just want to be good again.”

We can honor that voice, the human one, or keep listening to his disease tell us what it wants. Choose now. He can’t.

Joe Wankelman is an accomplished leader merging military precision with corporate innovation, excelling in data analytics, machine learning, and large-scale operations. He has honed analytics at Amazon via TLG, audited startups at Keiretsu, championed mental health at KIKO during COVID-19, and advanced community leadership as Snohomish County Commissioner.

Pursuing a Master of Science in Data Analytics and Policy at Johns Hopkins University, Joe enhances data-strategy-policy intersections for impact. He seeks collaborations to leverage data for efficiency and growth in our resilient era. Let’s achieve new heights together.

COMMENTARY DISCLAIMER: The views and comments expressed are those of the writer and not necessarily those of the Lynnwood Times nor any of its affiliates.

Author: Lynnwood Times Contributor

4 Responses

Bureaucracy, stuffing everything into that big box sealed with red tape , including anyone with mental health and/or addiction challenges, without a place to call home, signed, sealed and stacked up in exchange for dollars, funding, faulty statistics. Great insight and well said commentary. Louder, next time, so the ones in the back, the ones who need to hear it, hear it!

This is the most truth I have read in a really long time. Note to add, all the hud housing partners receiving kick backs when residents are currently using which is against lease terms and a failed system that harbors addicts, creating a systemic problem instead of the stepping stone it’s intended.

Reagan closed the last of the numerous psychological treatment centers when he was President. Those Asylums failed, not for lack of patients, but for lack of concern, for social experimenting, a lack of funds, and outright cruelty. Add in, a lack of employees, and greed, the greed of those who were running them. So now what? The asylums were closed, the patients sent home or to the streets. They had no alternatives, no other places to send them, and everyone voted anyone with any good ideas out. Numerous programs were tried, but lack of community support, lack of government support, and a lack of Medical Organizational support doomed everything they tried. Families with any family member with any visible physical abnormality, or with any mental disability were shoved into the attic or the basement, or worse, out onto the street, because no one cared, and the family felt embarrassed.

Now those in need such as these, have to fend for themselves, and as you know that doesn’t work so well. Many Christian churches make programs to deal with some of the aspects, but they lack permanence and lack of professional people trained to deal with these abnormalities. Society still turns its back to them, almost entirely, bless those who do not, and offer to help as much as they can.

It’s like trying to explain “National Insurance” programs. They are supported through taxes similar to how Social Security is handled. You don’t pay insurance healthcare premiums, instead the money is paid into national healthcare programs. There could still be the healthcare corporations to pick up the loose ends and you would be free to add them to your healthcare needs. That could include mental healthcare as well. Society funds them, and is hardly aware that they are. No profiteering medical persons can exploit the programs, no experimentation on the patients. Just an idea…

You’ve identified the core historical failure that still haunts us today. When deinstitutionalization happened without creating the promised community mental health centers, we essentially abandoned people with severe mental illness to the streets. The asylums were indeed cruel and needed closing, but we threw out the baby with the bathwater: the concept that some people need intensive, long-term support to function safely in society.

Here’s what’s working now that builds on your national insurance idea: Some communities are creating “care campuses” that combine healthcare, mental health services, and transitional housing in one location. Unlike the old asylums, these are voluntary, community-integrated, and focused on eventually transitioning people to independent living when possible. The DMIS system I mentioned could connect these services while giving clients control over their own data and treatment plans. When someone in psychosis arrives at the ER, instead of the current 72-hour hold and street discharge, they’d enter a continuum of care funded through pooled resources, similar to your national insurance concept.

The missing piece isn’t just funding but coordination. Churches and nonprofits you mentioned often provide excellent peer support and community, but they operate in isolation from medical services. Imagine if we combined their trust-building capacity with professional psychiatric care, all coordinated through a unified system where the person owns their treatment history. Add in supportive employment programs and graduated independent living options, and you have something that addresses both immediate crisis and long-term stability. This isn’t warehousing people like the old asylums; it’s creating a scaffold of support that people can climb toward independence, with some needing more rungs than others. The key is making it voluntary, dignified, and actually focused on recovery rather than containment.