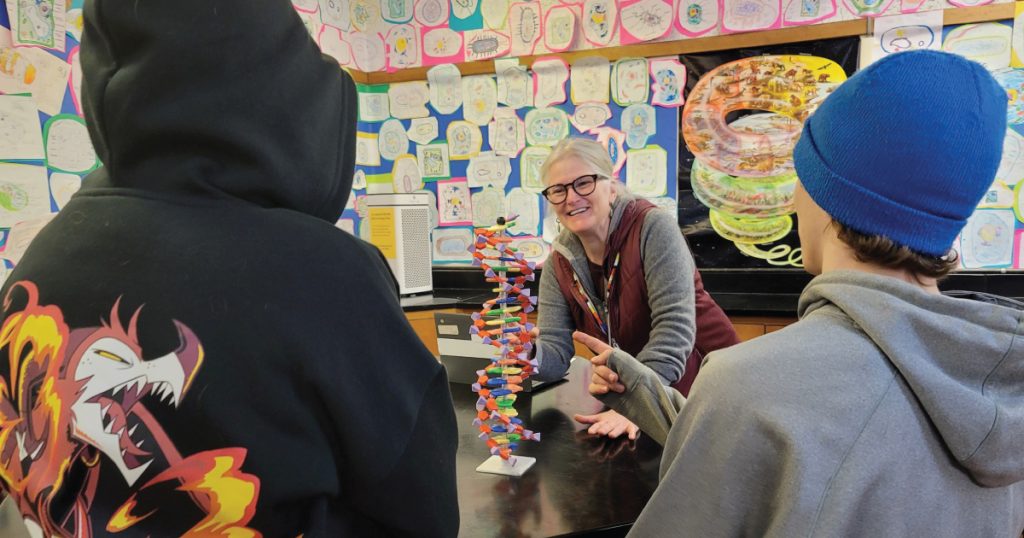

Holly Koon struggles every day in her 9th-grade biology classes to help students achieve, but sometimes it seems like a losing battle. Chronic absenteeism, growing class sizes and fewer classroom helpers all get in the way of student learning, she said.

“All students can absolutely learn, and they can learn to standard,” she said. “I have a biology class right now with 36 students in it; I have one instructional aid. How do you – in 60 minutes a day – individualize and support all 36 students?”

Koon’s question is one that echoes across Olympia this Legislative session as Democrats and Republicans debate how to spend dollars dedicated to education. Fueling that discussion is a national assessment that shows 71% of Washington eighth graders are not proficient in math, compared to 58% in 2013.

Although Washington is doing better than the national average, State Superintendent of Public Instruction Chris Reykdal agrees that student performance needs to improve.

“We have to make significant gains in elementary and middle school math in order to set up our students for maximum success in high school and beyond,” he said.

His plan includes fully funding basic education, including materials, supplies and operating costs and special education.

Reykdal said the difference between what the state supplies districts, and what they are spending on materials, operations and special education totals more than $800 million.

Democrats agree with Reykdal’s assessment. At a recent rally, Sen. Jamie Pedersen, D-Seattle, said: “There is nothing more important for the state government than to provide ample funding for the education of all kids who reside in the state of Washington.”

Republicans say they agree funding is an issue but Rep. Drew Stokesbary, R-Auburn, said legislators should carefully target new spending.

“The Legislature needs to acknowledge the reality and the highly disproportionate balance of power between teacher unions and the school districts,” he said. “If we just write blank checks to the districts, that money will go to teacher salaries.”

While Stokesbary is happy teachers have “one of the highest average teacher salaries” in the nation, he says money should be spent more directly to improve student outcomes.

For example, House Bill 1832, sponsored by Rep. Michael Keaton, R-South Hill, wants to tie teacher bonuses to test scores.

Under his plan, National Board-certified teachers would no longer receive extra money. Instead, money would be given to schools based on student reading achievement, and bonuses dispersed to teachers who contributed to helping students meet those standards. Some schools would also receive grants to hire reading coaches.

The bill also requires third graders to pass a statewide standardized test, pass an alternative assessment or provide a portfolio that proves “sufficient third grade reading skills” or be held back a year.

“Once you hit third grade,” Stokesbary explained, “more and more of your education becomes increasingly self-directed. If you can’t read at grade level – in third grade – you’re not going to be able to read your social studies textbook or your science textbook.”

Educators and Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction (OSPI) officials couldn’t disagree more. National Board bonuses for teachers were implemented to encourage teachers to improve their skills, which leads to higher quality education, and studies show holding back students who don’t meet grade level objectives hinders student performance.

“With adequate resources, schools can provide additional support and interventions to students without holding them back a grade,” said OSPI’s Chief Policy and Legislative Affairs Officer Jenny Plaja.

She added funding tied to student achievement would help higher-performing schools only and punish the under-resourced schools.

Koon agrees. She called the bill “destructive.”

“[HB 1832] will very likely result in better math and reading test scores,” she said, “and a less educated, less prepared-for-the-world student body.”

Studies tend to support Koon’s view. Student performance is often influenced by things beyond a teacher’s control, like poverty, learning disabilities, unstable homes and poor nutrition, research shows. Teaching to the test, as it is commonly known, tends to narrow learning to test prep questions at the expense of broader explorations.

A bill from the Republican side of the aisle getting support is SB 5007, sponsored by Sen. John Braun, R-Centralia. It provides funding to help reduce chronic absenteeism, defined as those who miss more than 10% of school days, excused or unexcused. Districts with low student performance often have high percentages of chronic absenteeism, OSPI studies show.

In Koon’s Mount Baker School District, 37.4% of students were chronically absent last year, so she is teaching about two-thirds of the curriculum she did 15 years ago.

“I just can’t move fast enough,” she said. “How do you keep up when these 10 kids are absent yesterday and a different 10 kids are absent tomorrow?”

Ultimately, Koon said student performance will improve if adequate resources are dedicated to classroom instruction. Koon recalled teaching a class of 28 students who all needed individualized instruction because of learning disabilities and all but three met the state performance standard at the time. The difference between now and then? That classroom, she said, had two certificated teachers – herself included – and three “top-notch” paraeducators.

The article was authored by Taylor Richmond of the Washington State Journal, a nonprofit news website operated by the WNPA Foundation. To learn more, go to wastatejournal.org.

Author: Washington State Journal

One Response

Reykdal is the problem.