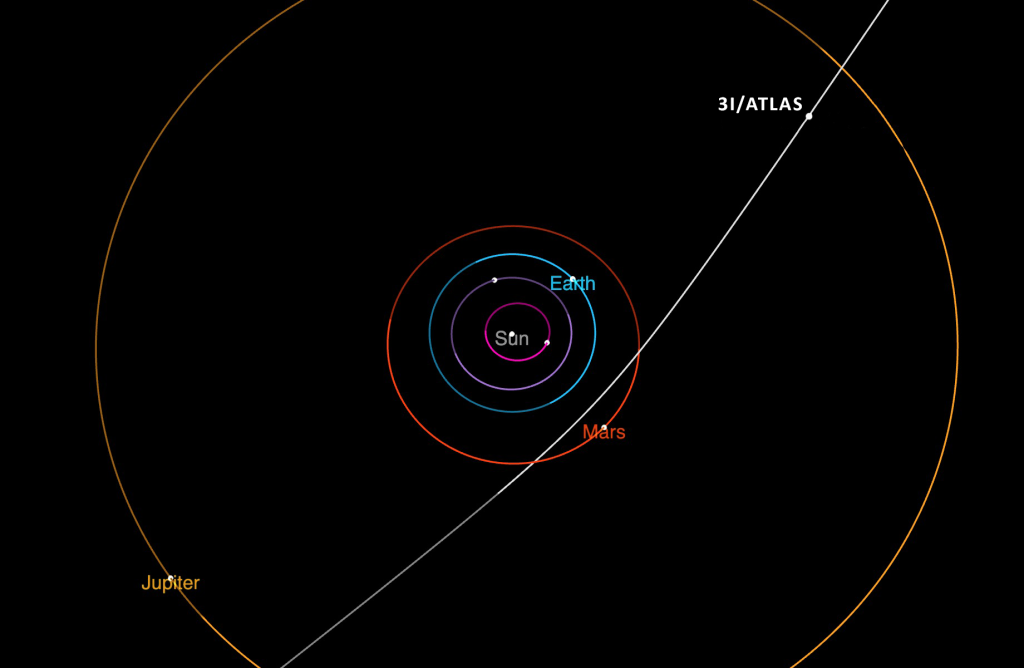

Interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS, the third confirmed object from outside our solar system to visit the inner planets, will reach its closest point to Earth on Friday, December 19, at a safe distance of about 167 million miles (1.8 astronomical units). An astronomical unit, or AU, is the average distance between Earth and the Sun—approximately 93 million miles.

Discovered on July 1 by the NASA-funded Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System (ATLAS) telescope in Chile, the comet has followed a hyperbolic trajectory, confirming its interstellar origin. It passed closest to the Sun on October 29-30, at about 1.4 AU just inside Mars’ orbit, and has since been speeding outward.

NASA officials emphasize that 3I/ATLAS poses no danger to Earth. “There is no danger to Earth from this comet, which will come no closer than 170 million miles,” NASA has stated in updates on the object’s path.

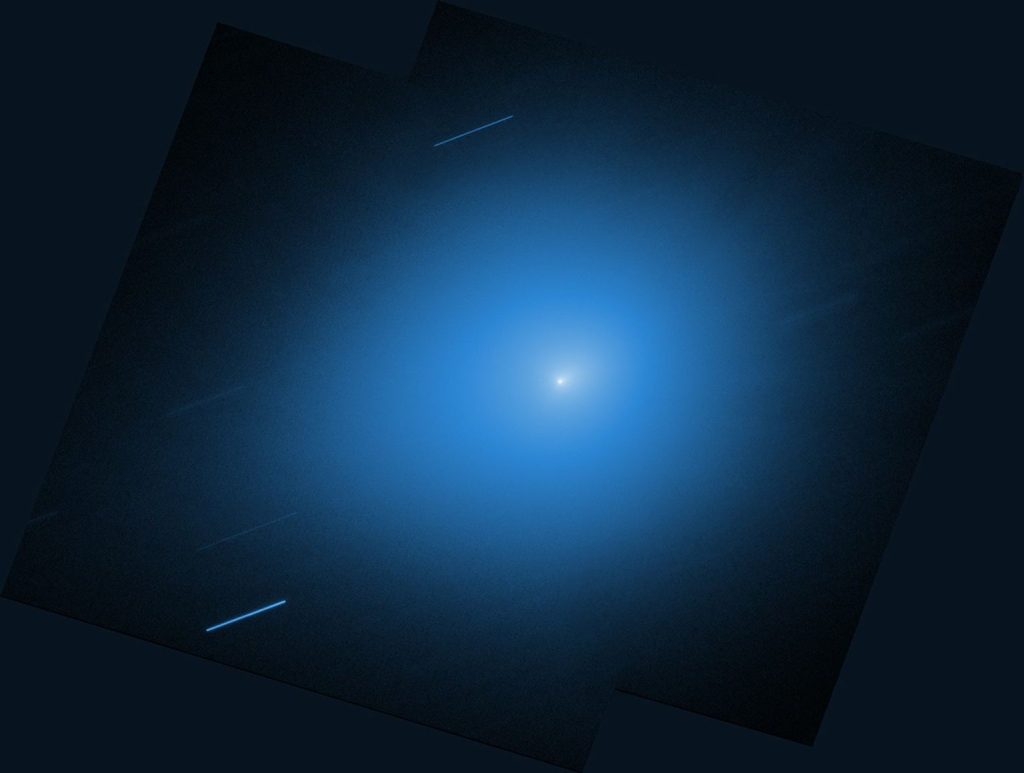

Recent observations reveal intriguing details about the visitor. Hubble Space Telescope images from November 30 show a coma of dust and gas, with the nucleus estimated between 1,400 feet and 3.5 miles wide. The comet has displayed activity including emissions of carbon dioxide, water vapor, cyanide gas, and atomic nickel vapor.

Geophysicist Stefan Burns, who has analyzed the comet’s characteristics in online updates, described recent color shifts in a video discussion.

“The evidence suggests that 3I/ATLAS was once probably a short-period comet around its host star and it was heavily thermally processed,” Burns said.

He noted the object’s organic-rich composition and a shift toward yellow or golden tones, that are possibly attributed to nickel emissions and exotic materials accumulated during its interstellar travel. Burns has also discussed potential links between the comet’s passage and solar activity, though astronomers attribute heightened solar events to the current solar maximum cycle.

After passing Earth, 3I/ATLAS will approach Jupiter in March 2026 before departing the solar system permanently, likely by the mid-2030s.

Amateur astronomers with larger telescopes may spot the faint object in the predawn sky, though it remains too dim for naked-eye viewing.