SNOHOMISH COUNTY—At the beginning of the year the Snohomish County Health Department experienced a 100% turnover in its food permit application review team leading to an unprecedented backlog of nearly 100 new businesses awaiting approval before they could open. Through a strategic plan, and reallocating resources, the Department has brought that number down to 36 but it still says staffing shortages need to be addressed to maintain its current response time.

There were over 300 employees when Dennis Worsham, Snohomish County Health Department Director, left the Snohomish Health District to pursue a position with King County in 2005 before returning to Snohomish in 2023. Right before the pandemic hit in 2020, the Snohomish Health District laid off 106 employees—two-thirds of its workforce at the time—the largest turnover rate Worsham has witnessed in his 30-year tenure working in public health.

What the pandemic taught the public health sector, however, is the need for its services and the need for a restructured model.

There are 35 local health jurisdictions in the state of Washington and Snohomish County ranks last in investments per capita. The Snohomish County Health Department remains one of the lowest funded local health jurisdictions in the state of Washington, when taking into consideration the county’s roughly 867,000 and growing population.

“Part of the challenges we had was trying to rebuild, and I think this is one of the opportunities coming in as an independent district into the department, is trying to figure out how to right the resources that we need to do,” said Worsham.

Approximately 85% of The Health Department’s funding comes from grants—not a stable revenue source—so the big push is figuring out a system of core funding from state and local governments, Worsham added. The fees charged by the agency does cover some of its services, but the Department has made the decision to be a full fee recovery program, meaning it does not require fees to fully cover some services related to environmental health.

No local funding, other than a one-time American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) dollars, have supported the Department’s Environmental Health program.

Snohomish County is Washington State’s third largest county and has over 3,500 permitted food establishments. On average, the Health Department sees around 47 food permit applications a month that are currently reviewed by only two staff members and a supervisor. At the beginning of the year, both of those two staff members left their roles, one through a promotion and the other leaving the agency all together.

What’s more, the agency shared, was that reviewing food permit applications is a lengthy and complex process, and fulfilling vacancies require a time to bring the new hires up to speed.

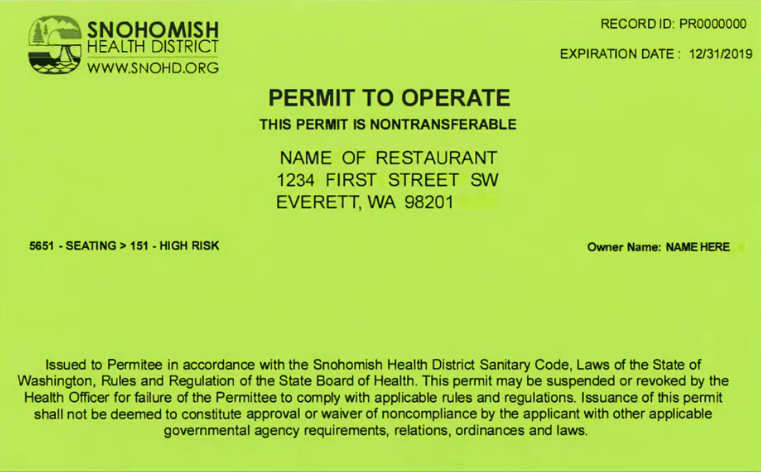

In that food permit review process, the Department adheres to the state Board of Health-adopted food code and different establishments have different qualifications based on whether the foods served is considered high or low risk. A coffee shop, for example, is considered an establishment of low risk; whereas a restaurant that serves meat, cheese, and eggs would be considered high risk requiring proof of refrigeration, temperature checks, and so on.

“It’s not like we look at a plan and say it’s approved or not approved, it’s literally walking through a checklist that they have to provide all of the information based on the risk of the food that their serving, in the criteria of each of those areas…For a county this size you’ve gotta have more than two people who are doing that work. For one, if you lose one you lose 50 percent of your capacity. In our case we lost two, we lost 100 percent of our capacity,” said Worsham.

The role of these workers does not end with approving food permits. After a restaurant opens, inspectors continue to visit their operations to ensure they are doing whatever they need to do to remain within safety food codes. The team conducts approximately 550 restaurant inspections in a single year.

The Department advertises a twelve-week turnaround for processing food permit applications, however there is no maximum timeframe processing requirement. When the Department lost their two staff members, this timeline jumped to 20 weeks.

The Department began to implement a variety of mitigation strategies to reduce the timeframe to process food permits with a turnaround goal of 4-6 weeks by the end of September. As of August, the Department is below the initial 12-week timeline, averaging about 10 and a half weeks.

The Department now has 36 pending permit applications in queue as of Thursday, August 29 with 98 in active review.

When the Health Department announced that it would be making that shift from independent District to county-owned Department back in May of 2022, it cited the ability to leverage the county’s resources as a driving factor. While the Department has received county backing to combat the opioid epidemic, Worsham informed the Lynnwood Times it has not received any additional funding for its food permitting services.

Though its food permit department is fee-based, it still could benefit from an additional county-funded FTE positions of which Worsham plans to address the Snohomish County Council on promptly before County Executive Dave Somers presents his proposed budget in September.

If the Department were able to maintain its two food permit review positions and add a third positions from its plan review, so that losing one staff member would not result in losing 50% of capacity, it believes staffing would be more than efficient to decrease food permit processing down to a four-week turnaround.

The county’s current proposed public safety sales tax, which will be left to the voter’s decision this November, could not be used for food permitting work. However, core functions of public health are in the domain of injury and violence prevention, Worsham noted. If the tax is passed, The County’s Health Department would receive dollars to develop and implement a program that would address the increase of youth violence in Snohomish County. The program would take a public approach in reducing community violence and increase community well-being and safety, Worsham said, adding that this a role local public health should be doing and currently isn’t because the agency lacks the capacity.

How to Eat Safer: Understanding Food Establishment Permits

Author: Kienan Briscoe