EVERETT, Wash., June 25, 2023—Marilyn Quincy, 79, is a name so ingrained in Snohomish County history that it’s difficult not seeing her and her family’s influence in the region.

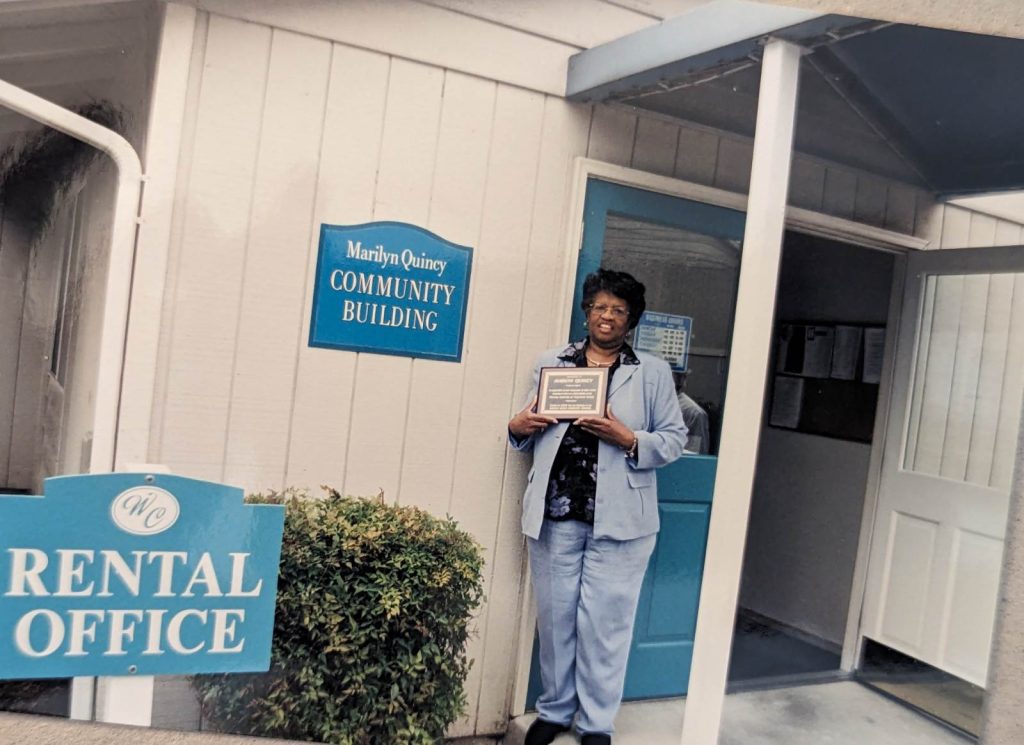

From William P. Stewart Highway in Everett named after her great grandfather — a Black Civil War veteran who fought for the Union Army and was part of the Illinois 29th Colored Infantry; to the Civil War memorial in Snohomish also honoring Stewart; to the county’s annual Nubian Jam event; to the Marilyn Quincy Community Center in Marysville; to the Snohomish County Black Heritage Committee (SCBHC); to the way the Everett Public Library assembles its historical archives, Quincy has had, and continues to have, a tremendous impact on shaping the area since her family first settled here in the 1880s before Washington was a state.

Recently Quincy was awarded the Legacy Award, appropriately named the Marilyn Quincy Award, at the Snohomish County Black Heritage Committee’s annual Red and White Banquet on April 29. The award was in partnership with the city of Everett and an associated plaque will be displayed somewhere in the city at a yet-to-be-determined location, memorizing Quincy’s great work for years to come.

“It’s an honor to get an award while you’re still alive for legacy,” said Quincy at the award ceremony. “When my family was here before the state of Washington really was a state, they looked forward to having a better life for themselves and their offspring. I want to say that their offspring are doing well here…I am so proud to look out here and see all those people part of the legacy of Snohomish County and are carrying on.”

Quincy had always known her family had deep roots in Snohomish County. Her mother was born in Everett in 1918 and knew that her grandparents, at least, had lived in the county for years. Her great grandfather, William P. Stewart, is buried in the Grand Army of the Republic Cemetery in Snohomish.

When Quincy was a child, her family had the tradition of visiting cemeteries on Memorial Day to pay respect to veterans. During these visits her mother would frequently say: “one of these days I’m going to go to Snohomish and see if I can find my grandparents grave,” but she never had the chance.

In 1993, during Everett’s centennial anniversary, Quincy began researching her family’s history in preparation for an exhibit the city was holding, honoring resident’s families who lived in the area around the time Everett became a city. Quincy thought this would be an appropriate time to carry out her mother’s wishes in locating her great grandparents, to gain a better understanding of when her family arrived in town. She found them at the Grand Army of the Republic Cemetery in Snohomish, where her grandfather, who served in Illinois’ 29th Colored Infantry, was memorialized as a war hero.

The 29th U.S. Colored Infantry, which was Illinois’ only Black regiment during the Civil War, arrived at Galveston Bay, Texas on June 18, 1865, and was present at the first Juneteenth on June 19, when Major General Gordon Granger read General Order Number 3 informing its residents of the end of the Civil War and slavery was abolished.

Pleased to learn this, Quincy then took her research further at the Everett Public Library but was surprised to hear there was little record of Blacks living in Snohomish County at the time. She knew she had to take matters into her own hand.

“Her tracing of early Black families has given me so much hope because I’ve known there has been Black people in Snohomish County and Everett since the early colonization of it but nobody was really collecting or telling their stories; the fact that she was able to go back and look through those records and find those is super impressive,” Lisa Labovitch, History Specialist at Everett Public Library, told the Lynnwood Times.

Labovitch explained that historically, archival records collect media written by White people for White people and there hasn’t always been great documentation of Black History. Quincy helped changed that through record collecting of her own, reshaping the way the Everett Public Library has continued to collect records today.

Researching further, Quincy learned that her great grandfather was living in Snohomish County around 1897 although she believes he came much earlier. Her grandfather, for example, contributed to the Census when Washington became a state in 1889 so she knew her family was living here then.

Through genealogy, Quincy learned her family originated from Wisconsin where her great, great grandfather was recorded as one of the first people to buy land in the Cheyenne Valley. Quincy also learned that her grandmother’s family — known as the Shepherd Family — came from slaves and were brought to Wisconsin, by their master, to set them up with a new life.

Somewhere down the line the Shepherd family moved to Washington, settling near Monroe, although Quincy has yet to find the reason why in her research. According to the 1889 census, there were three black families in Snohomish County: The Udells in the Edmonds area, the Richardsons in Monroe, and the Stewarts near Snohomish.

Apartments in Marysville was renamed the Marilyn Quincy Community Center in her honor. Photo Courtesy of Marilyn Quincy.

“Quincy is such an awesome lady; at her age to be so meticulous and so intelligent, and so honest, and so kind. That’s just who she is,” MaryAnn Darby, Executive Committee member for the Snohomish County Black Heritage Committee told the Lynnwood Times. “And she’s been so instrumental in ensuring her heritage is remembered, and the community is remembered, and African American people are remembered.”

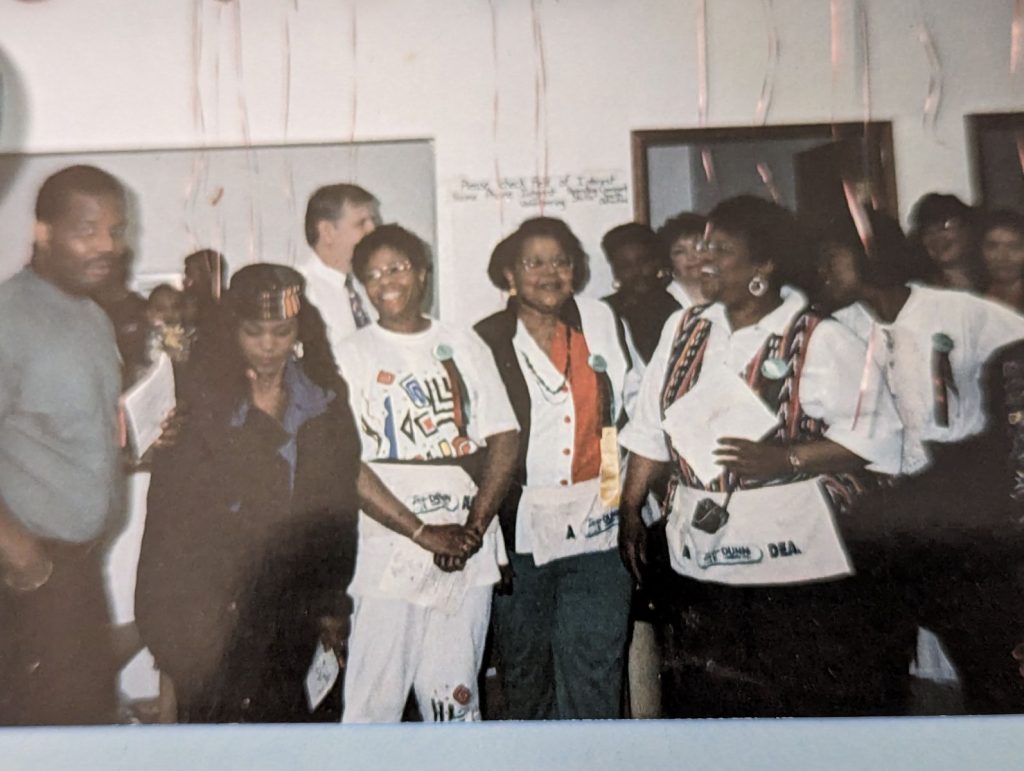

When Quincy was younger, there weren’t many other Black families in Snohomish County, so many would get together for picnics on the fourth of July. Prior to that, Black families in the area would seldom see each other, only at funerals, and according to Quincy, the Fourth of July picnic was a way to have a sense of community and check-in with one another in a more jovial setting. One of these gatherings came to be known as Nubian Jam, on July 3, 1993, that paved the way for the eventual founding of the Snohomish County Black Heritage Committee.

“I have known Ms. Marilyn Quincy since I was a little girl,” DanVonique Bletson-Reed, President, Snohomish County Black Heritage Committee wrote in a statement to the Lynnwood Times. “In fact, I have known her for as long as the Nubian Jam has been in existence. Ms. Quincy has been a pillar in our community for many years and it has been a pleasure learning from and serving with her to help make Snohomish County a better and richer place for its residence.”

Quincy has endured her share of discrimination over the years. After high school she encountered difficulty landing a job. When visiting the employment office, she was told the only place that was hiring Black people was the Scott paper company and nursing homes. She chose the nursing home route where she worked for three years.

While working at the nursing home, Quincy, who shared with the Lynnwood Times she was overweight at the time, began taking an interest in nutrition and enrolled herself in Everett Community College to become a dietician.

Shortly after, she saw an ad for her dream job — working as a dietician at a local hospital. She called the hospital, explained her qualifications, and was told she would be a “perfect fit,” according to Quincy, and to “get right down here for an interview.” When she arrived for an interview, however, the employer said they could not hire a Black person, Quincy told the Lynnwood Times.

The incident landed Quincy on the news about six months later. In that report, the hospital explained they had hired a Black man during World War II who had taken a knife and threatened his employees. They swore to never hire a Black person again. Later, the hospital was ordered to come up with an affirmative action plan but by then Quincy had her reservations based on her past experience.

She decided to try her luck at the Boeing company instead, where she worked for three years. During this time her husband, also a Boeing employee, was transferred to Everett so she followed — being closer to where they lived in Snohomish County anyway. The couple worked opposite shifts, with Quincy working nights and her husband working days — a scheduling conflict that “wreaked havoc” on their marriage, she told the Lynnwood Times.

She soon quit her job with Boeing to further her education, while working as a cashier at Safeway. As far as she knows, she was the first Black cashier at Safeway although Safeway’s Media Relations team was unable to confirm this with the Lynnwood Times.

Throughout the years, Quincy also served on the Board of the Snohomish County Immigrant and Refugee Forum where she helped refugees from other countries acclimate to life in Snohomish County, was on the board of M2 Job Therapy where she helped inmates of local prisons develop job hunting and life skills to successfully transition upon release, was on the Workforce Development Board where she researched the labor market and even established training programs to encourage businesses to move into Snohomish County, and worked on the Dislocated Worker Program that helped people whose jobs had been eliminated by plant closures or large downsizing learn new workplace skills, learn job hunting skills and work with employers to hire them.

“On behalf of the City of Everett, we’d like to express our appreciation for Marilyn Quincy and acknowledge the major impact she’s had on our community. Ms. Quincy has dedicated much of her life to helping others and being an advocate for African Americans in Snohomish County and beyond. We are proud to have awarded Ms. Quincy the first ever Quincy Award for her years of service. Thank you, Marilyn,” Simone Tarver, on behalf of the city of Everett and Mayor Cassie Franklin, told the Lynnwood Times.

Quincy is active in her church (New Life Everett) and has been able to go on mission trips to Mississippi to build houses with Habitat for Humanity and distribute food, and the gulf to help with the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. She has also been able to help with local needs through several other church projects.

For her outstanding achievements in her career in the Employment Security Department, and contributions to the to the quality of life in Snohomish County and Washington State, Marilyn Quincy was honored and recognized in 2007 by the Washington State Legislature with House Resolution 4649 that was introduced by then-Representative John Lovick.

“Marilyn Quincy is an exceptional individual whose dedication and passion have left an indelible impact on her community. Through her tireless efforts, she has become a beacon of inspiration, leading by example and uplifting those around her. Marilyn’s unwavering commitment to serving others has not only transformed lives but has also created a ripple effect of compassion and positive change in Everett,” Tyler Chism, Placemaking Manager for the City of Everett Economic Development, told the Lynnwood Times.

7 Responses